Every song knows its home

Karolina Grzywnowicz in conversation with Bogna Świątkowska

-

Bogna Świątkowska: Your several week-long stay in Palestine, in the West Bank, came about through an open call for an art residency in Ramallah. I know it was your first encounter with this complex part of the world. What was your proposal?

-

Karolina Grzywnowicz: I think that going with a preconceived project to a country that you’ve never visited before isn’t a right thing to do. I wanted first to expose myself to what I’d see and experience there, to the stories and conversations. But the procedure is such that you need to submit at least a concept note. So I described a project I’d been working on for a couple of months, Every Song Knows Its Home, where I collect immigrants’ amateur songs. I trace them in various archives, but also do field recordings. Sung in different languages, originating from different regions and traditions, the songs deal with the general experience of migration. Sometimes this is the story of a journey, an expression of homesickness, or an account of how people try to cope in the new conditions, building a new life for themselves. I thought it very important to start the proper work on on this project in Palestine, where so many people have lived in refugee camps since 1948.

-

-

Even though their home towns or villages are to be found not thousands or hundreds but sometimes just few dozen kilometres from the place of their exile, they can’t return to them. They can look at them at Google Maps. Their stories are incredibly moving, yet it’s clear that it’s not emotional reactions they want, but for the occupation to end. I’ve seen you at work, and I know that you spend a lot of time researching and gathering information. Reading, talking to experts, interviewing local people. Did any of the meetings that you had there prove a breakthrough, a turning point?

-

Let me tell you about two. The first one was with Ehab, who was my guide around the Amari refugee camp. At the end of our first meeting, he told me, “You know, in fact we live under a double occupation. We are occupied by Israel, but also by our own government, which doesn’t care about us. We’ve been left to our own fate. We have no representation.” Many people there, not only in refugee camps, were critical of the government, but Ehab put it most bluntly. I saw the diplomatic district where government officials live. I didn’t expect such luxurious homes, such wealth in Palestine. Especially that the district is located just three or four kilometres from the Jalazone refugee camp, one of the largest, where the situation is particularly difficult because a huge Israeli settlement, with a population of some 6,500, is virtually next door. For many Palestinians, the diplomatic district is a symbol of official corruption and of politicians’ being out of touch with everyday issues, a measure of how much they’ve stopped representing the people to focus on the pursuit of privileges for themselves.

-

The second meeting was when we were recording in Balata, the largest refugee camp in the West Bank, near Nablus. There I met an incredible woman. Tohfa is a teacher of the Arabic language, a very warm and generous person, endowed with a great voice. She sang absolutely beautiful songs for us, and told us stories about how she and her family, using the fact that they had a permit to go to hospital and were able to enter Israel, went to the Sea of Galilee, where she comes from, and there they all sang songs about the Nakbah, about what they’d lost and about how one day they would return. They sang and cried.

-

During my meeting with Tohfa, I also recorded the lullabies that she sang to her kids. And then I thought that this was an important theme, that I wanted to start recording lullabies in refugee camps. Most people in such camps suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder and have trouble sleeping. The Israeli military usually arrives at night. That’s when they search homes and make arrests. The refugees are never sure if they can fall asleep. Sleep deprivation is part of their reality. Even having moved out of the camp they sleep two to three hours a day and only when they decide they can afford that. To sleep in those conditions is a luxury and an act of bravery.

-

-

In Palestine, contact with daily life and with how – despite everything – people cope with it is surprising for an outsider. But it also restores your faith in humanity, in the human ability to make life meaningful even in the face of most unfavourable scenarios. You’ve been to very many refugee camps. You’ve seen how people live there. What in particular held your attention?

-

Everyday forms of resistance are an interesting subject.

-

-

It’s actually the title of this residency.

-

That’s right. Being there, one sees practically nothing of resistance in the military, violent sense of the world. When you think of Palestine, certain images, familiar from media reports, play out in your mind. It’s worth remembering that the image of Palestine we know is largely constructed by Israel. Since the occupation affects absolutely all aspects of Palestinian’s lives, doing anything is actually a form of resistance. The very fact of staying there and not leaving is a form of resistance. There’s even an Arabic word for that – sumud – enduring, persevering. Anything you do can be considered in terms of grassroots work and resistance. It can be gardening, upcycling stuff, collecting water, or cooking together. Or singing songs together. Anything you do that performs presence and cultivates customs is an act of resistance against the process of being erased from the landscape, from history, from the map.

-

-

Such as using the herbs and spices featuring in traditional Palestinian cuisine, which it is illegal to forage. Such regulations seem absurd: the malice of depriving people of what has been a traditional component of their diet is yet another way of “cleansing” the territory of its hitherto inhabitants.

-

I devoted a large part of my research to plants that can serve as an illustration of Israeli colonialism and occupation. Today those most hotly discussed are thyme, sage, and a plant called akoub. All three have been used to season Palestinian dishes since times immemorial. Thyme makes part of zaatar, a universal spice, sprinkled on all kinds of food, eaten with bread and olive oil. Sage, or maramiya, is also a staple spice, with sage tea being very popular. And akoub (Gundelia tournefortii) is a plant that grows only in the wild, like an artichoke with thorns. Palestinians know exactly where it grows, when and how to forage it without damaging the root so that it can spring up again next season. Picking akoub is a feminine task, often a source of extra income for those women whose husbands are in Israeli jail. They pick the akoub, remove the thorns, and cook delicious traditional dishes with it that take all Palestinians back to childhood. So these three plants are an important feature not only of the Palestinian landscape and cuisine, but also of the Palestinian identity. And all three have now been listed as protected species, their foraging prohibited. You can pay a heavy fine or go to jail for the possession of even a very small amount of either of them. Rabea Eghbariah, a Palestinian lawyer living in Haifa, who deals with zaatar-related cases, told me that as punishment for the possession of prohibited herbs, Palestinians’ cars are seized and held for months or even years inside fortified Israeli settlements. There’s really no reason for these plant species to be listed as protected. There had been no research indicating that their populations were shrinking. Thyme and sage are common throughout Palestine. Akoub, which doesn’t appear in Europe, grows only in spring, but the Palestinians know exactly when to forage it, they’ve been doing it for centuries. Listing those plants as protected species is an example of Israeli greenwashing. Outside, it looks like a noble deed – protecting nature – which resonates fully with the Western world, whereas it’s actually yet another way of uprooting the Palestinians. In a similar vein, Israel has been setting up national parks and nature reserves, ostensibly for environmental reasons, in reality to seize more and more territory inhabited and used by the Palestinians.

-

-

Being pro-environmental is one of the highlights of Israel’s political marketing narrative: about the Middle East’s sole democracy, which not only respects, but actually embraces Western values, such as ecology. What can art do here?

-

That’s a tough question. And I guess I should honestly say that I don’t know. I’ve kept considering my own position and my right to talk about what I’ve seen and heard there. How to avoid abusing it, exploiting it? What can I add, what kind of perspective, experience? What can we give each other, learn from each other?

-

I know for sure that I don’t want another project about refugees where you talk about them and for them. Every Song Knows Its Home is meant as a kind of platform to make their songs, their voices more audible. I search for those songs in dusty archival boxes, and I record them with people whose voice is being silenced. Tohfa from Balata told me at the end of our meeting: “Tell them in Europe what we experience here, tell them how our life looks like because we can’t. We can only tell you how it looks like and you can pass it on.” They are really aware of how easily they can be erased, which is why they try to give as precise an account as possible to anyone willing to listen.

-

-

Translated by

-

Marcin Wawrzyńczak

-

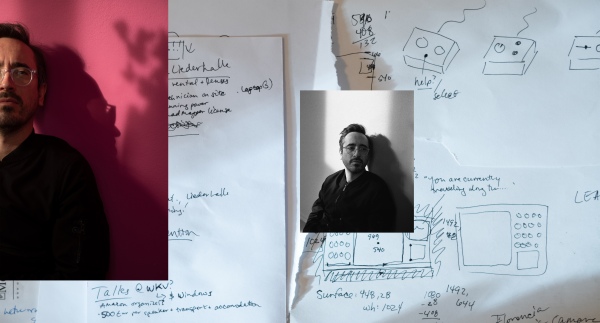

Karolina Grzywnowicz on a residency at the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art (August–November 2019). Film: Marta Wódz