Ursula Mayer

What Will Survive of Us

Rachel Hill

What Will Survive Us...

...is becoming an increasingly common refrain. As staggering biodiversity loss and accelerating mass extinction becomes a constitutive component of climate anxiety, the question of what can endure planetary-scale devastation becomes a beseeching demand.

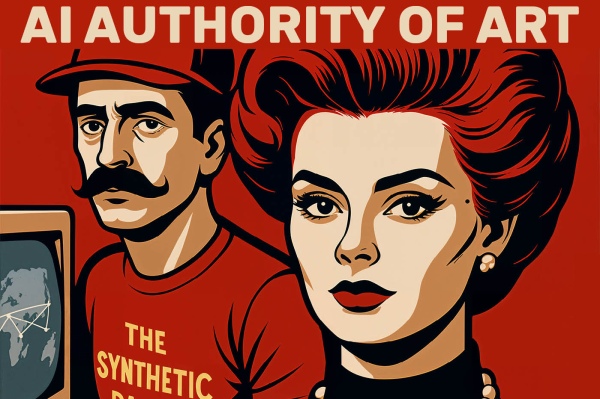

The work of Ursula Mayer has long addressed issues relating to the entanglements of environment, cinematic form and posthuman subjectivity, primarily realised through the moving image medium. And yet, Mayer’s work refuses to be circumscribed by the contours of conventional cinematic form. Instead, her work unwinds itself from the delineations (and delimitations) of the screen, curling into sculptural systems and coiling into all-encompassing installations. Through these unravelling and remixing forms, Mayer’s artwork blurs distinctions between bodies, spatialities and subjectivities.

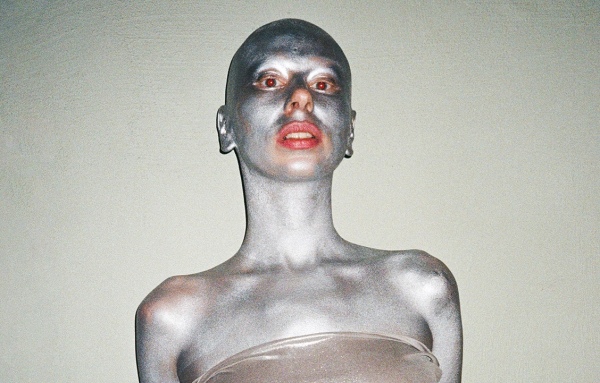

In What Will Survive Us these twinning theoretical and formal concerns materialise in myriad, multiscalar ways. Throughout, the role of hybrids become a uniting force, instantiating philosopher Paul B. Preciado’s concept of “techno-living systems” (2008). Following technoscience scholar Donna Haraway’s emphasis on the inseparability of nature from culture, as demonstrated both in her framing of “naturecultures” (Haraway, 2003) and in her infamous figure of the cyborg (Haraway, 1985), Preciado’s techno-living systems highlight the imbrication of all life with technological infrastructures and processes.

The floating figure of Mayer’s long-term collaborator Valentijn de Hingh loops in two of the exhibition's video works, mimicking the player at rest function commonly found in video games. Dislocating this virtual protocol away from the playspace of video games, and into the fluctuating worlds of the exhibition, re-renders such repetitions as a meditative repose. Incorporating the screen upon which the video is played, these artworks coalescence into an extended contemplation of the figure of the posthuman.

Mayer’s work assails the notion of a consolidated cohesive self so central to european humanism and its enlightenment legacies. Humanism (as its name suggests) privileges human exceptionalism, to which all life is subordinated. It is an epistemological framework in which all materiality is instrumentalised as raw matter, waiting to be given meaning through its deployment and formatting within human metrics of need, modes of quantification and regimes of qualification. But who is the human of humanism? The parameters through which the valourised category of the human is policed are very tight and typically idealised as male, able-bodied, white and wealthy. The world of enlightenment humanism is controlled and conditioned by the universalisation of these very contingent stories around what the human is, and thereby designed to fulfil the needs of a specific few.

Mayer’s hybrids contest the validity of humanism's stable subject, through emphasising the malleability of bodies and the fluidity of subjectivity. As such, What Will Survive Us is a posthuman exploration of the potentialities of bodies, matter and subjects, rather than a consolidation of the pre-determined and exclusionary configurations of humanism. Key to the exhibition then is the modelling of other, posthuman stories. These new myths move outside the ostensible ineluctability of pervasive stories rooted in humanism, to instead envision other ways of being.

*

Current environmental decline is the detourmont of a very particular story, a story which weaves together the legacies of enlightenment humanism and escalating industrialisation. A focus on the specificities of these dual conspirators highlights what environmental historian Jason Moore has observed, that “the crisis we are experiencing is not a failure of species, it's a failure of system” (2019). The anthropocene centres the Anthropos – a consolidated species-level figure – as responsible for environmental collapse, thereby obscuring the culpability of specific nations in engineering the untenable present. Rather than maintain and reinforce this equalising fallacy, Moore argues for the “capitalocene,” that is, the geological age induced by the ideological and material operations of capitalism. The particular iteration of world which is currently hegemonic is therefore produced not solely through humanism's exclusionary discourse but also through capitalist modes of qualification.

Professor Melinda Cooper has written compellingly about how, when faced with the material limits of the planet, advancements in biotechnology helped to engineer new forms of resource capture by “digging down into the generativity of being” (2007). The capitalocene thus does not only exploit and imperil life on Earth, but also leverages new technological means through which to optimise the productivity of that life's expressions and mechanisms. The world of the capitalocene, with its planetary derangements and violently inventive mining of life, seem inescapable. However, as Ursula K. le Guin as stated: We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art.

What le Guin elegantly makes clear is this: when we speak of fiction we parlay with the possible, pushing at the parameters of the thinkable, agitating at the borders of being and taunting the inevitable with its own contingency - to render it mute. Stories which reimagine life and its parameters are predominantly the realm of science fiction. With its methodology of speculation, science fiction enables the sculpting of futures, solidarities and ways of being which exist beyond the seemingly incontrovertible foreclosures of the present. When mobilised as a means of dissent, science fiction, with its alternative ways of thinking and different potentialities for feeling, stages the fight of stories against stories.

*

What WIll Survive Us takes the radical potentials of science fiction in order to configure life and its parameters differently, outside of the debasements of humanism and the exploitations of the capitalocene. Crucial to this engineering of the otherwise is the exhibitions mobilisation of Zoe. The posthuman transspecies force known as Zoe is theorised by feminist scholar Rosi Braidotti as: “a materialist, secular, grounded and unsentimental response to the opportunistic transspecies commodification of Life that is the logic of advanced capitalism” (2013). The reorientation of understandings of life, away from the capitalocene’s atomisation and towards “ecologies of belonging,” emphasise how we are united across the profundities of matter. As French theorist Gaston Bachelard as observed: Matter may be given value in two ways: by deepening or by elevating. Deepening make it seem unfathomable, like a mystery. Elevation makes it appear to be an inexhaustible force, like a miracle. In both cases, meditation on matter cultivates an open imagination (1983).

The mysterious and the miraculous: sensitisation to the endless generativity of matter comes when rethinking life as Zoe. What Will Survive Us fabulates with Zoe in order to develop a new science fiction mythology of and for the future. Throughout the exhibition, recourse to Zoe becomes a means of re-imagining how life is predominantly conceptualised. Rather than individual bodies and individuated selves, the vitalist life force of Zoe is an embrace of life as a multiscalar process of perpetual becoming and endless modulation. Through this countervailing genealogy, the future becomes a shifting polymorphic and protean web, full of possibility. Consequently, the exhibition mobilises a methodology through which to build counter-memories, other ways of being in, with, and beyond the world which challenge the reductive ratiocinations and imaginaries of the present. Through this conceptual creativity and fictioning, a more viable world of interspecies solidarity can be glimpsed. Conjured through this dreaming of the otherwise, these other worlds envision what will survive us...