talk

„The language that speaks us”

Adelina Cimochowicz in conversation with Romuald Demidenko

-

Romuald Demidenko: Thinking back to the moment to the first lockdown, I remember when we talked over the phone about our collaboration on the project. You told me what you were planning to show, and mentioned a table in the garden that visitors would be able to “climb” onto in order to view from this vantage a film – a situation happening between several participants of group therapy. Your three-channel installation fills the exhibition space almost completely, and we view the protagonists from up close. Why the decision to present your new work in this manner?

- Adelina Cimochowicz: I wanted for the visitor to be able to watch each of the interlocutors. Hopefully, dividing the projection into three screens would produce a sense of being in the middle of the discussion. This, I hoped, would force us to decide whom we follow, whom we give our attention to, knowing that it means ignoring the others. At the same time, and even more importantly perhaps, I wanted an effect that would produce a sense, perhaps not of being ensnared, but of literally being overwhelmed by the situation shown in the film.

-

The exhibition features a video called, in Polish, Utrata, an ambiguous title that can be interpreted in various ways; the simplest explanation would be that it stands for the name of a small river flowing near Warsaw, but the word also means “loss.” Can you expand on the location and the title?

- The title came precisely from the river, which flows through the historical park of the now-defunct Neurosis Treatment Centre in Komorów. The name seemed a perfect commentary on what mental healthcare could look like and what it actually looks like in Poland today. The challenges are mounting, and fast. Ever year, 1.5 million patients are treated at psychiatric hospitals in Poland. Between 1990 and 2004 the figure rose by 0.9 million, the sharpest such increase in Europe. According to the Ezop report on mental health in Poland, some 10 percent of the population suffers from various forms of neuroses. The data I’ve managed to research suggest that before the transition there were places in Poland where therapeutic methods were developed that paid attention to the social situation of mental patients, their place in the community. Today, thirty years after the joyous return of capitalism, the discourse of mental health and work methods is is strongly informed by neoliberal ideology, and issues such as background or class affiliation have all but disappeared from the discourse.

-

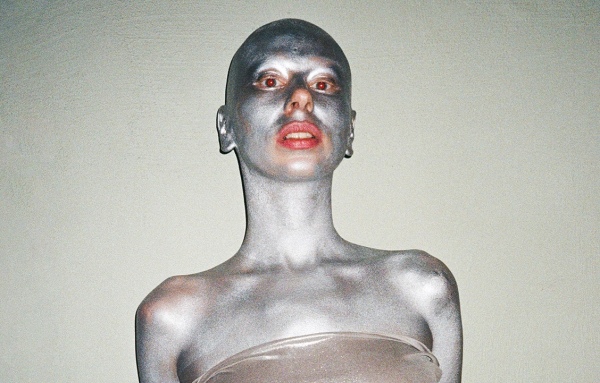

You decided to work with professional actors, spent two intense shooting days with them. The scene that exhibition visitors get to see in the Project Room can be said to represent only a fragment of that encounter. Can you share some of the behind-the-scenes aspects of your collaboration?

- I decided to work with professionals because they are trained to experience the emotions being enacted, or acted out. From the very outset I was interested in constructing moments of strong tension. I realized that I had no competences to take responsibility for a situation involving persons without professional training.

- Before the shooting, we’d held half-improvised rehearsals with the actresses and actors where we creatively intervened in the script. When we met for the actual shoot, we based exclusively on it. Apart from the intro, the film is almost completely a single continuous take. So the two days of working together were devoted to repeating it over and over again. In the exhibition, we show the final effort, a closure to this process literally and symbolically. The very fact of secluding yourself, even for two days, with a group of people and working intensely together produces a sense of belonging, and the people you spent time with become sort of a temporary family. Everything is squeezed into this particular time and space – a unique, very powerful feeling.

-

Who are the characters shown in the film, and how to interpret the scene that unfolds between them?

- The characters have their origin in the book Returning from the Land of Fear by Andrzej Rogiewicz. They are based on the former patients of the Komorów hospital, who are described in it, albeit rather laconically, by a therapist. Based on those descriptions, we tried to develop each of the characters. I guess – I hope – there is no single interpretation of the situation that transpires between them. Working on the script, I was reflecting on difficulties of communication, on issues involved in joining a group, on the position of the Other, on language that eludes us, that speaks us rather than being spoken by us.

-

Some say we are already experiencing a “depression epidemic,” and it’s not the first time that you address the issue of anxiety disorders, whether through your own observations or personal experiences.

- The number of people suffering from all kinds of mental disorders has been steadily growing, and there’s no doubt that’s an effect of the late capitalism that we live in. We talk quite a lot about diseases of affluence, much less about how they are driven by this particular system. When I finally admitted to myself that, euphemistically speaking, I’d lost it, realizing that I wasn’t alone, that there were many of us, that we shared this experience, often caused by very similar if not identical factors, was very comforting. But continued severe stigmatization of mental disorders as well as the neoliberal narrative of individual responsibility mean that persons suffering from such issues very often feel alienated, guilty of what they are experiencing. I feel like that very often myself, even if I’m able to explain very nicely where this feeling comes from, what it’s connected with.

-

Working on the project, you mentioned you were looking for a language to talk differently about the mental-health crisis. Could you elaborate on that?

- The simplest answer would be that dealing with topics related to emotions, to mental disorders, is a kind of self-therapy. And until some time ago I’d certainly have said so. Today, however, it seems to me to be something quite the opposite, something that may at times aggravate issues rather healing them. Naming emotions or expressing them visually is probably a rather easy gesture to make, one that separates you from the burden. And then you can talk at length about how it allows you to examine it, to gain a perspective, to understand. I’m convinced, however – and I deeply believe – that publicly talking about disorders or mental diseases, about their experience, creates a space for becoming closer with others, for mutual support and concern, and finally for the recognition that it isn’t so that we’re abnormal, that often we simply function in structures that violence is inscribed in, and it is for changing these structures that we must fight together.