Ewa Czwartos

-

Graces and Gorgons

-

On Ewa Czwartos’s exhibition Vitruvian Woman

-

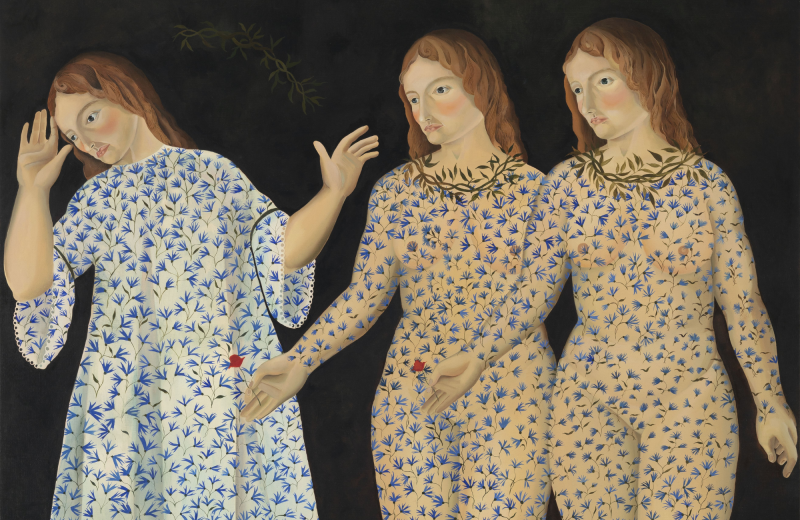

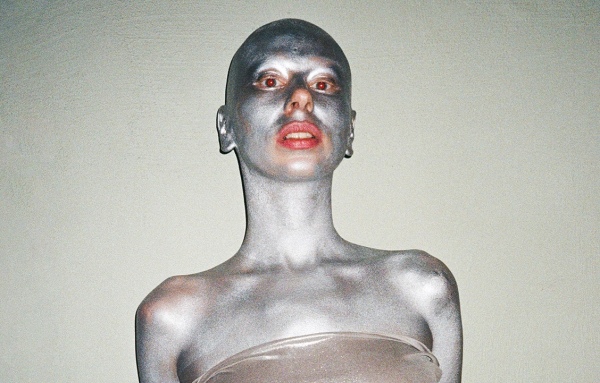

Painted by Raphael, they reflected the canon of female beauty. In Rubens’s paintings, they already mocked the canon: sensual, self-confident, they demanded the right to be imperfect and came to life. The Three Graces. Inflected by all cases, brought to life and reworked in every way by contemporary art, they would put on dark glasses, but they have never been as dangerous as this. In Ewa Czwartos’s canvases, you will not see Joy, Radiant, and Blossoming. The women painted by the young artist have a determined expression on their faces. Their eyes seem empty, but their gazes are paradoxically penetrating. These are the emotionless faces of models. They were someone’s daughters, wives, lovers. They were harlots, saints, and madonnas. They lived in Greek and Roman myths, adorning vases and tapestries. They stood in the light and allowed themselves to be enclosed in frames. Anonymous. They disappeared, died in childbirth, or went out into the streets. Joy. Radiant. Blooming. Similar one to the other, to the third, fourth, and fifth. Multiplying endlessly, duplicating patterns, adapting to the expectations of the world arranged for them by men. The embodiment of mythical female grace and beauty. The embodiment of beauty in the Greek understanding of ideal proportions. The artist calls them “Vitruvian women” – beauty resulting from the maintaining the right configuration – as in the famous drawing of a naked man inscribed in a square and a circle. However, in relation to the position of the woman, the configuration is a broad, or perhaps one should say: heavy metaphor. Maybe they shine in these paintings, maybe they are at this moment of blooming femininity described by court poets, but they are certainly not radiant. They are not even sad, rather defiantly indifferent. They line up in fearsome rows. Maybe they are manifesting indifference to the centuries when they were pelted with flowers. They were decorated and styled like exclusive utility items.

-

In the painting provocatively titled Burlesque, women with Renaissance bodies have been equipped with faces and hairstyles from the 1920s. The title itself suggests that the configuration of these bodies should be interpreted as dancing. For a moment, the Graces become girls, girls from a cabaret, whose bill has not changed much since antiquity. If they dance, it is certainly for men. However, in Czwartos’s paintings, their naked bodies are adorned with cornflowers instead of sequins and feathers – a symbol of fertility and a timeless token of searching, not so much for love, but for a husband. For women in the 1920s, marriage was in a sense a path to freedom. They broke away from their father’s tutelage, became respected women, and because of that they were somehow less suspicious. At least from time to time they were let out of sight and if they kept up appearances they could live their own lives for a while. Unless they couldn’t. From father’s house to husband’s house – always someone’s, always on a chain. It doesn’t matter whether it is the 16th or 20th century. There will always be those who say that a woman’s destiny is to do this or that. And destiny is a curse. The bodies of the women depicted in the painting are wrapped in thin barbed wire - a subtle yoke, so natural, at first glance it is a branch of a bush. Something between wire and a thorn bush, practically invisible among all those flowers. On their wrists and necks you can see thin white bands. White as collars, like clean cuffs. Thin as a leash. Functional like bands for tourists using the all-inclusive offer. Because everything is for them when they are for everything. They have everything when they have to do everything. Under the curtain of cornflowers, their bare bottoms are red, as if they have just been spanked. Or maybe it was a solid beating? The Roaring Twenties gave women a lot of freedom: they could work, show their legs, and dance modern dances. But in the daily newspapers, the joke about beating your wife had its permanent place, just like obituaries. Graces and girls laughed at men’s jokes. Just out of politeness.

-

Centaurea Cyanus takes its title from the Latin name for cornflowers. Blue flowers in Ewa Czwartos’s paintings are a motif that recurs, or rather is repeated consciously and with emphasis. It is not an ornament, but a stigma. It looks innocent, just a feminine pattern, and yet it holds in itself all the power of old beliefs, the mysterious power of superstition. “She who finds the most bluebottles while working in the field will have a quick wedding.” Cornflower, a field weed, a symbol of modesty – a Prussian virtue, the favourite flower of the German Emperor Wilhelm I. It brings to mind other Prussian virtues: straightforwardness, piety, discipline, reserve, and a sense of duty. Cornflowers decorate the bride’s simple shirt. The Graces standing next to her may be her bridesmaids – naked, but all in cornflowers. With laurel wreaths around their necks, but the laurel on a woman’s body in Czwartos’s art always resembles a crown of thorns. There is another expressive flower in this painting. It is a poppy, a symbol of death. A gift for the bride. A warning, an announcement of necessity or perhaps consent to the sacrifice, because after all the bride is sacrificed, her father giving her away to the husband at the altar.

-

The titles of Czwartos’s paintings are significant and often emphasize the mysterious. Non Omnis Moriar – five figures wrapped in delicate lace, a bit like a torn net or spider’s web. Czwartos also works with animation and in a way incorporates the technique in her painting, applying successive layers to her figures, masking nudity and at the same time exposing it. So there is lace-net and floral decoration, with a touch of the innocence of white flowers, with pink and red-red flowers scattered here and there, with green shoots playfully covering smooth pubes, masking nipples. Is it a veil interwoven with flowers, or a net in which these tailless Sirens were caught? Only after a while do we notice that the protagonist of the painting – multiplied, in five persons – holds a dagger in her hand, aimed at her own breast. Five silver daggers: five elegant and unobtrusive suicides. The dagger looks like a gadget, and the whole thing like another dance routine in a Renaissance revue of female statues. Renaissance and surrealism have never been so close – and so close to reality. The image is powerfully attractive: it works without any explanation and is enough on its own, but if we go deeper into the layers of meaning of this pictorial animation, we can discover that the face under the modest cap (of a wife? a swimmer?) is from a painting (1530–1532) by Lorenzo Lotto. Kept in the National Gallery in London, it is known as Portrait of a Woman Inspired by Lucretia. But who was Lucretia? Today, it is Wikipedia where we find solutions to 16th-century riddles:

-

Lucretia – a legendary figure from the 6th century BC. She was the daughter of the Roman patrician Spurius Lucretius Tricipitinus and the wife of Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus, cousin of King Tarquinius Proud. In her husband's absence, she was raped by the son of Tarquinius Proud, Sextus Tarquinius. She could not bear the shame and committed suicide, having previously told everything to Collatinus. According to legend, this became the direct cause of the outbreak of the uprising led by Brutus, which resulted in the overthrow of the monarchy and the establishment of the republic in 509 BC. Brutus and Collatinus became the first consuls of the republic.

-

The libretto of the opera The Rape of Lucretia by Benjamin Britten is based on the story of Lucretia, as well as Shakespeare’s poem of the same title.

-

Using this face, lending it to the characters of the Graces/Sirens-suicides, is an expression of painterly erudition and is well thought out. Lotto painted an anonymous woman in Lucretia’s ornate Roman dress, holding a drawing in her hand, in which a naked Lucretia raises a dagger to plunge it into her heart. Her hair is loose, and she covers her womb with a hem of fabric. Under the drawing in the painting, the painter placed an inscription with a quote from Titus Livius, the famous historian, author of books on the history of Rome. The Latin maxim Nec ulla impudica Lucretiae exemplo vivet translates as: “No unchaste woman shall live by Lucretia’s example.” The allusion to rape is reinforced by a sealing wax flower – in Lorenzo’s painting it lies on the table, next to the inscription. In mythology, this flower symbolizes the sexual assault of Hades, the god of the underworld, on Persephone. How to interpret this? Perhaps: Immodest women who have suffered rape are to blame themselves, even death will not wash away their shame? Ewa Czwartos gives her protagonists a face from Lorenzo’s allegorical painting, and on the lace net enveloping their bodies she adds flowers that may be sealing wax flowers, and sums it all up with a bitter, ironic title: Non Omnis Moriar. When it comes to a man, the master, this maxim sounds lofty, that is obvious. However, when it comes to a woman, things get complicated. “I will not die entirely,” the artist wants to say on behalf of the anonymous protagonists. I will not die entirely, because the shame will remain.

-

Rooted in mythology, the history of Rome and the history of painting, Czwartos’s patchwork, read with attention, becomes a highly topical statement – a manifesto, a strong voice of feminist discourse. We discover that the artist’s technique – these borrowings, multiplications, mixing fragments of the bodies of different women from different paintings – this sewing of a female figure from pieces of other figures – is not just a formal procedure, but carries a clear message. The artist says that she puts these women together like Frankenstein – the mad scientist in Mary Shelley’s novel. From one head, from another hand or foot – selected pieces of many ideals from the canvases of the masters become the starting point for deconstructing the canon of female virtues and duties. The concept of femininity shows its monstrous beauty and infinitely replicated artificiality. These dangerous images seduce and this is their witty, elegant revenge on the history of the female nude.

-

The artist plays freely with traditions and freely deals with the masters. She delivers critical arguments with a polite smile. Four Graces for Raphael is a playful gesture of the painter, who, drawing from the history of art, simultaneously analyzes it and judges it. This treatise takes place exclusively on the visual plane, but the language of symbols is clear and moving. The English titles sound neat, but the point here is rather to emphasize the topicality and ironic tone of the painterly commentary. The painting entitled Strangers clearly carries an ironic message. Five figures – Graces/girls/madonnas – this time with a face from Raphael’s painting Lady with a Unicorn. There is no full agreement among art historians on what the unicorn was supposed to symbolize, whether virginal purity, pregnancy, or perhaps unspoken female desires. They stand in a row, with their hands on their shoulders, in a gesture that is both defensive and decisive. On their statuesque bodies, on their smooth foreheads, red marigolds – an innocent pattern or, as the artist says herself, a deadly rash; in Mexican tradition, marigolds are called flor de muerto, flower of death. Lace collars encircle their necks, fabrics draped over their thighs, covering the demonized “womanly shame” and bringing to mind the garment of the crucified Christ – there is a subtle blasphemy in this seemingly random stylization. The female figures are supposedly the same, but one of them has blue skin, clearly darker. The question: Who is the stranger here? This image accurately challenges stereotypes, mocking them intelligently. Because they are all strangers, because in patriarchal culture, it is the woman who is the Other. In the culture of ancient Greece, from which all of Europe grows, a woman, although she has many graces, is not a human, nor is she an animal. She is the property of a man, like animals and children. When she wants to have her own opinion, wants to stand up for herself, in the eyes of male society she becomes a monster, a furious Harpy or Hydra: when her head is cut off, three new ones grow. According to one interpretation of the myth, Hydra was the personification of the water priestesses of Lerna. The story of Heracles killing Hydra may therefore be a story about the desire to eliminate this cult and conquer the sanctuary by invaders. Jess Zimmerman, American poet, author of the book Women and Other Monsters. Building a New Mythology, draws attention to the fact that mythical stories about female monsters are narratives created by men: Ovid, Homer, Hesiod, Virgil. The harpies described by Virgil in the Aeneid are greedy, screaming birds with female heads. They throw themselves at Aeneas and his crew, who land on an unknown island, find oxen there and kill them to satisfy their hunger. The revellers grab swords to cleave the hideous creatures and it doesn’t occur to them that it is the daughter of the king of this island who has come to guard her property; for the stolen cattle belonged to her. When she defends her own, she becomes hideous. And all of her sisters grow claws and tails. In the canon of patriarchal culture, Gorgons, Sirens, Harpies, then witches, whores, and devil worshippers are women who get out of control. They defend their property, cross borders, raise a cry. It’s their determination and independence that makes them monsters.

-

Heroic traits in women are very out of place; they immediately turn them into strange monsters. It is women like this who make a revolution. And the largest painting (composed of two parts) in Ewa Czwartos’s exhibition – in this melancholic, bitter reflection-filled revue of female beauty – is titled Revolution. The artist doesn’t show us angry Sirens. Those who go to the barricades are still beautiful. Importantly, they are dressed. Their dresses have strength, they are exuberant, there is vitality in them, some strange excess. The dresses do not hold back the fighters, do not bind them. They are like banners, like wind, like troubled water. They raise their hands, fold their fingers – they demand a voice, but this gesture seems vulgar, it is a manifesto. This is no longer a row, it is already a march, already an army. All under one face – Lucrezia de’ Medici, daughter of the Duke of Florence. The face is taken from a Renaissance portrait, painted – the matter is uncertain – either by Bronzino or by Alessando Allori. This Lucrezia did not have a happy life either, an early, arranged marriage became her prison, she died young and immediately there were rumours that she had been poisoned on her husband’s orders. In this way, Czwartos deals with yet another dangerous myth – the myth of the princess, instilled in generations of girls by fairy tales, fables, and Disney films. All these stories – the patterns and narratives of the male-centric system that permeate our culture – make up the “Vitruvian woman.” You can admire these images, appreciate the artist’s talent, imagination, and craft, but you can also study this exhibition as a feminist treatise or an essay on the history of women in art history.

-

-

Joanna Oparek

-