Between art and activism

Grayson Earle in conversation with Klara Czerniewska-Andryszczyk

-

Do you consider yourself a digital native?

- I think so. I mean, I certainly had a life before the internet, but since my dad was also in software, I had access to it before most people in the States (and probably, in the world). I grew up in a remote town in the mountains of California. There was absolutely nothing to do except going outside (which I didn’t feel like doing sometimes) and playing – and hacking! – video games.

-

So that’s how you have ended up teaching game design, right?

- Yeah, among other things. My latest position was lecturer at Parsons School of Design in the game design programme.

-

It is said to be the best art and design academy in the US.

- Right, and it also costs $50,000 a year to go there (laughs). As a comparison: I used to teach at the New School (Parsons) and at the City University in New York at the same time. I was teaching exactly the same class, used the same syllabus, had the same number of hours; I was getting paid $3,300 for the semester at the City University, which is a public school, and around $9000–9500 at the New School. One way of looking at this is the demographics of the students: at the City University, my students were 80%–90% black, while at the New School 75% of them were white, which made me think that I was getting paid less money to teach minority students.

-

When did you start noticing such social and economic inequalities?

- I feel like I have always been an activist for one reason or another. I remember when I was in high school, I staged a walkout with some other students on behalf of the teachers there. Maybe it was thanks to my mom. She is a lawyer, but it was never about the money for her – she has been helping women, or domestic partners, go through divorce, making sure that they aren't left empty handed. So I guess some of my politics comes from her. And then, when I started university, I thought I was going to be a filmmaker, but ended up in the cinema studies programme instead. It promoted a Marxist and feminist methodology – I felt it was my level of analysis, and it became my world.

-

As a new media artist, you might become a billionaire thanks to the NFTs…

- That is an interesting point. The problem with the NFTs is that they represent this very old model of scarcity, applied to something that was inherently to be a space of non-, or post-scarcity. It is a good example of how the internet is prone to marketisation. This is really disappointing, because originally the internet was meant to be a place where ideas, images and sounds could be replicated, and now people are trying to bring ownership onto it. Also, the kind of work that gets produced in that space is very limited – as a blockchain artist, you’re not doing anything that wasn't possible before. On the other hand, however, there are artists like Sarah Friend, Primavera De Filippi and the art collective terra0, who are making very interesting blockchain work – things that are only possible in this new medium. In terra0’s project, for example, nonhuman agents are given agency thanks to software and the blockchain – that's the kind of work I find interesting, because it uses technology to outmanoeuvre the existing reality. That is how I came up with this software that bails people out of jail, Bail Bloc, which I have presented in the context of the Whitney Museum.

-

Do you produce any material works, or is it only digital and time based?

- With Bail Bloc, at one point I had a show at a private gallery and produced some objects for sale – the agreement always being that the money would go to bail people out of jail. However, in the end no-one bought any of the objects – which probably speaks to my inability to create something tangible for people to buy (laughs).

-

As an artist / activist, do you find dualism in your practice?

- I tend to think of it all as a unified thing. For me, it's all about cultural production rather than art practice. I think this is a more valuable way of looking at it, and also more inclusive. After all, the name of the game is to change culture.

-

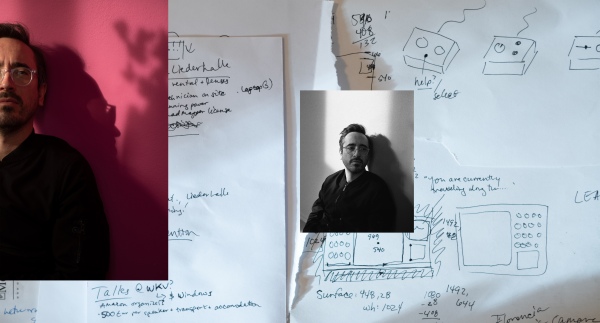

What's your goal for your residency at the Ujazdowski Castle?

- I am using it to finish up an exhibition that is happening two weeks from now in New York. I have one more piece to complete, a two-video installation about artificial intelligence and machine learning, which I was given a grant for. Apart from that, I will be working on my second video, which is going to be about the political economy of encryption: both the hardware it requires as well as the interesting philosophical aspects of it, including the question of power structures. For that piece, I am hiring a composer for the first time – it will be interesting to have an intentional soundtrack alongside the video.

-

Regarding your creative practice, do you prefer to work alone or in a more collaborative manner?

- I prefer to work collectively, in a way that reacts to the circumstances. I have a collective in New York called The Illuminator. We do guerrilla video projections and shows and we have held a lot of residencies together – the latest one was at the Hemispheric Institute at the NYU.

-

Can you tell me how The Illuminator started?

- It was during Occupy Wall Street. I was there from the very first day. I actually came there, because I read a memo in the Adbusters magazine: “September 17, Wall Street. Bring a tent”. And that was all. I didn't know anyone else who was going, I was pretty new to New York. I stayed for the night and eventually ended up there for several months. I joined the media team. And suddenly we went from being 50 people in a park to being all over the news across the country. At some point, someone – I think it was Mark Reed, the founder of The Illuminator – convinced Ben of the Ben and Jerry's company to donate $50,000 to buy a van with a very powerful projector on top. We started projecting “99%” everywhere, as a way of bringing attention to the movement. Since then, the project has taken on a much more diverse role, from self-generated activities to operating as a kind of a megaphone for interesting movements and organisers.

-

What is your goal?

- The idea is to get into the press cycle the night before they would have covered the event – we intend to keep that event in the public imagination by doubling down on it and creating a kind of counter-spectacle. From there, we work backwards, asking ourselves about what headline we would like to achieve, what we want people to think, and the next question is what sort of image we would produce that would attract the attention of the newspaper. That is the most energising and fun thing for me, I think.

-

The form of projecting texts on buildings resembles the works by Krzysztof Wodiczko…

- Yes, I was certainly familiar with his work when the group was started. Typically, however, what people bring up in this context is Jenny Holzer. It's funny because our work is so similar to hers – if I didn't know any better, I would say it’s totally derivative of hers (laughs). But none of us knew her back then. We knew Krzysztof Wodiczko, the Guerrilla Girls, and then we ended up with something that looks so much like Jenny Holzer’s work (laughs).

-

What are the repercussions of your political involvement?

- I was once arrested for projecting onto the Metropolitan Museum, during David H. Koch's dinner party organised to celebrate his $60 million donation to the museum. It was a clear sign for me that we had pissed them off to a degree that they were not going to just absorb the press. I believe that museums really value their image – and a threat to that is something they take very seriously.

-

On the other hand, acting as a collective gives you the power of anonymity.

- I believe that creating the society we want can't be done anonymously. With the hacking of Hans Haacke, which I did during his retrospective at the New Museum in 2019, I felt that it was important to be named – which is also why I was then able to be investigated. On the other hand, however, working as an anonymous collective is beneficial in case you are breaking the law or doing something that might get you fired. It is also a way of amplifying what you're doing – a collective becomes a sort of superhero, you don't know who or where they are. Even the sound of the name – The Illuminator – evokes a feeling that they are everywhere, they can be any one of us.

-

And it could also be just one person, pretending.

- Yeah!

- Warsaw, 14 October 2021