Art as a Form of Belief

Alicja Wysocka in conversation with Krzysztof Gutfrański

-

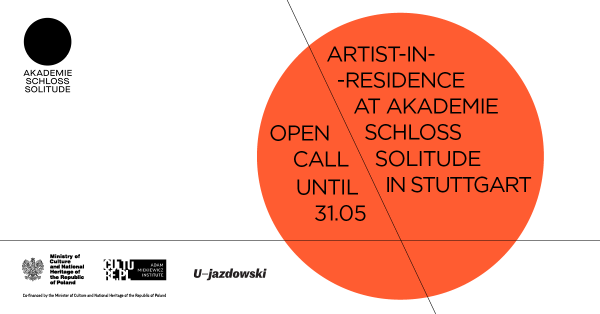

In 2020, you participated in an artistic residency as part of the Eastern European Network’s Akademie Schloss Solitude programme in Stuttgart. How do the categories of Mitteleuropa or “Eastern-European artist” relate to the artists of your generation? How do you understand them in the context of your own creative practice?

- Studying in Germany and working on projects outside Europe encouraged me to re-examine my Polish identity. This coincided with working on the first edition of Przesilenie [Solstice] in 2018. In a nutshell, it was an open event referring to the Slavic custom of celebrating the changes of seasons, i.e., Kupała night [the shortest night of the year celebrated in the Slavic tradition as Kupała night – ed.]. Our event, organized with Joanna Rajkowska in Nowogród, was related to the local history of the oldest Rural Women's Circle [Koło Gospodyń Wiejskich, KGW] in Poland, celebrating its 74th anniversary in 2021 and an ancient mound hidden behind a massive church. There was no sign or signpost and I looked for a way to get to it for a long time, but finally Joanna (Rajkowska) took me there, you have to go through private land, which at the end turned out to be private property [...]

- Several experiences led me to this project. After returning from Brazil and working in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro in 2016, my main plan for 2017 was to travel through various villages in Poland. I had a suitcase with different kind of ropes and other art materials; I offered art and craft workshops (on macrame technique) to people living in villages of Budy, Kuźnica, Saczkowce, Dzieczewo, Paliwodzizna, Macikowo, and Nowogród. It was a form of research, a chance to talk to people and explore new places, but also to re-examine Polish peripheries. I remember the countryside of my childhood — Pustków, Zaklików, Irena... It was also interesting that the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship has the highest concentration of Rural Women's Circle in Poland, and that even such a modest village as Nowogród is home to this mound — an early settlement from the Iron Age.

-

-

-

Photo: Yulia Krivich

-

-

What reactions did you meet with?

-

A bald woman with a suitcase full of different kind of ropes, what does she want from us (laughter)?! In Nowogród, however, it just clicked, straight away. I borrowed a bicycle from Joanna and invited myself to people’s houses for tea. It was great, I love tea prepared in this communist- style glass with a saucer and served with homemade cake. Joanna laughed that she had finally gotten to know her neighbours thanks to my encounters with them. For me, as an artist interested in social practices based on collaboration, the convergence of these two facts has stimulated my imagination as a space of influence. A tiny village as the hearth of people working together. As I mentioned, Joanna lives in Nowogród , and together we decided to create the first edition of Solstice. We wanted to gather people at the mound and place a sculpture-hut that we created together on the top. Since the history of the settlement and the village dates back to pre-Christian times, we thought we should hold this event on the day of the summer solstice, which was celebrated by the Slavs as closely related to the cycles of nature. I knew Parandowski’s mythology [the most popular edition of Greek mythology in Polish – ed.] and all Greek gods by heart, so I began to wonder what happened to the knowledge of Slavic mythology and why isn’t it taught in Polish schools.

-

-

You stayed at Schloss Solitude during a very specific time. What did you want to work on, and what did you manage to achieve in Stuttgart?

-

The fact that Stuttgart is the second-largest city in Europe after Budapest in terms of the abundance of mineral and thermal waters fascinated me. However, I found only three swimming pools with mineral water in the city. I managed to visit two of them (the third is under endless renovation) just before the lockdown. I also tried to find drinking water fountains, once very popular throughout Stuttgart — it was also rather difficult. There is no map, even for tourists, which would list such places. Many of them are difficult to find, and the ones I did manage to locate are often architecturally interesting; unfortunately, most of them aren’t working. Stuttgart could stand to gain a lot from promoting this tradition. The awareness of the enormous amount of water flowing underground greatly influenced my imagination.

-

-

What does one do at an artistic residence in the middle of Covid-19 lockdown, in a castle surrounded by forests, forty minutes’ walk from the nearest buildings?

-

Akademie Schloss Solitude is one of the few international residences that did not suspend its residency programme during the pandemic. It was very comfortable to be there in a safe institutional bubble. The forest was therapeutic. On the first day, walking down the straight path down the castle hill, I came across an Eastern European supermarket, Mixt Markt, which fulfilled my culinary dreams of buckwheat and pickled cucumbers!

-

We were a close-knit group of around twenty residents and it was good to experience living in such a tight community. For me, it was a time of calm and focus following a rather turbulent period. My head was buzzing with intense experiences, such as the second edition of Solstice (we invited, among others, the wonderful performer Maria Magdalena Kozłowska). My dreams were very vivid. Later, there was time for writing and planning new projects — including the next edition of Solstice, a project focusing on the idea of cooperatives, the Garden Gang project in Frankfurt am Main, where I am currently studying at the Staedelschule. I also rode my bike a lot.

-

-

Your previous work featured the theme of water and water-related cleansing, healing, and transformative rituals. You focus on the beliefs of the Proto-Slavs, contemporary visual culture and non-European beliefs. How do you pull all these threads together?

-

I have been researching water-related rituals for quite some time, as well as the importance of water in the social context — for example the Russian banya, where even politicians have met to discuss matters amidst its cleansing steam. By the way, I recommend a great book by American professor Ethan Pollock, Without Banya We Would Perish, published by Oxford in 2019.

-

My last exhibition in Frankfurt am Main discussed water as a carrier of trauma, but the beginning of these interests goes back to a traumatic childhood experience. My mother made an effigy of Morana for my older sister’s class [a pagan Slavic goddess associated with seasonal rites based on the idea of death and rebirth of nature – trans.] I watched rags, paper, and wood take the shape of a woman under my mother’s skilful hands. Morana had a white head made of a bedsheet. Her eyes and smile were drawn with felt-tip pens, the spreading hands made of paper were “crucified” with drawing pins on a wooden rack. Later, to the delight of children and teachers, the edifice was set on fire and drowned in a nearby river. The exhibition in Frankfurt was an attempt to reconcile this trauma, but also another experience related to water — the baptism ritual that forces you, without giving you a choice, into joining the Catholic Church. Just to mention, I started the process of apostasy five years ago. I was also inspired by one of the interpretations of this practice of drowning Morana. According to some, it emerged following the baptism of Poland (966), as a way of Slavs dealing with the traumatic experience of the destruction of all religious edifices — the representation of Slavic religion — by burning and drowning them. I am also wondering why this dummy drowned in the river has to be a representation of a woman [...]

-

-

- Photo: Yulia Krivich

-

Later historical tropes have certainly complemented Morana’s story. As we all know, witches do not float better than ordinary people. In modern times, the punishment for allegedly practising magic was the so-called ordeal of water — tossing the accused into a body of water. If she stayed afloat, she was guilty and would be killed, if she drowned, she died innocent. I wonder how you work with pre-Slavic traditions in this context. It is often difficult to find the right sources and know what the water rituals really looked like, since they have been gradually overwritten by successive traditions [...]

-

For me, the biblical tradition and Noah’s Ark, where God decided to drown disobedient people and only save the patriarch’s family, also reflect trauma and water correlations. Also, those who did not want to convert to Christianity were to be drowned. Another, more affirmative water ritual is śmigus-dyngus, adopted by Christianity in the form of Lany Poniedziałek [Wet Monday], originally associated with the rites of the vernal equinox and trivialized today. Dousing others with water was supposed to ensure prosperity, just like placing a straw miniature female puppet in a vessel of water for the entire winter, to ensure a better harvest. Today, priests consecrate harvest wreaths (which are, by the way, made by Rural Women's Circle for the local competition), just as those straw dolls were sprinkled with water in the past. After the dyngus, the boys walked around the village with one dressed as a bear, collecting favours, and later drowned the bearskin in the water. Did this bear at any point evolve into the straw effigy representing the woman, Morana? How did sprinkling for good harvest turn into a dramatic act of drowning? How did Morana, the Slavic goddess of the cycle of birth and death, become the evil lady of the winter who must be killed?

-

In relation to water, what surprised you during your stay in Stuttgart?

-

IImmediately after I arrived at Schloss Solitude, a bus passed through the main square and almost ran me over — it turned out that there was a bus stop there, right in the middle of the representative square! I quickly realized that this was a city for drivers, not pedestrians. It is also shocking that the locals do not use, or do not have the possibility to use, natural resources, that is the mineral and thermal waters. Instead, they have a river forced underground, flowing under a shopping centre.

-

-

How was life in Schloss Solitude, how did you spend your time around the castle?

-

The best part was talking, walking and cooking together (I was giving baking bread sessions), exchanging opinions and experiences. This is probably the best form of research. We went hiking, organized film screenings, and practised yoga. I really enjoyed one evening, the birthday of one of the residents, where everyone performed— danced, played or recited something.

-

I met a lot of great people — artists, researchers, writers, and dancers from all over the world. We are planning an exhibition with the curator Olivia Berkowicz, who was also a resident. It was supposed to take place in May in Schloss Solitude, but because of the pandemic it will take place in September most likely! [...]

-

-

And if you wanted to give us a virtual tour of the exhibition?

-

To some extent, I managed to do something similar at the Jo-Anne gallery in Frankfurt am Main. In front of the gallery, there was wood and chalk for drawing while sitting by the fire. You go down the stairs to the gallery; you can hear the audio before entering. I have a vivid memory of the Chapels of Skulls in Kudowa-Zdrój, also a spa town with mineral water — another strong childhood experience, related to religion and water correlations. I couldn’t believe it, how can one create a sacred place out of human skulls and bones?! I remembered this in relation to working on the exhibition in Frankfurt, I also thought about individual artistic practices as a form of building a religion. I imagined visitors to the exhibitions as those who would believe, or be seduced by, a certain narrative — or not. In this case, I see art as a form of religion that wins people over through certain practices.

-

Coming back to the exhibition: on the opposite wall of the gallery, there is a screening of a film I was working on in Germany. I created my first project from here. On the walls, there are ceramics created as props that I used in the film. This time I am reminded of the walking balls that I saw at Jasna Góra sanctuary, left there as votive offerings following the healing by miraculous painting of Black Madonna. I created ceramic bowls, goblets, soap dishes; various objects or devotional items for performing a cleansing ritual, baptism or just a relaxing bath. When planning the film, I thought of water as an element that binds religions and rituals of different cultures together, as a source of purification, but also trauma. Some pottery was not fired in the kiln, so the clay dissolved in the bath, contaminating the water, thus creating an inverted cleansing ritual.

-

Interest in pre-Christian / pre-capitalist rituals has always been present in modern and contemporary art. The current wave of spirituality is rooted in the exploration of feminism, anti-colonialism, and alternative systems of power. This manifests both in artistic practices and the gallery programmes. Do you think that pandemic fears strengthen the links between ritual/magic and art and politics?

-

Even before the pandemic, I managed to visit Morocco and Turkey and explore hammams and public baths, and make the installation Make Love not Art, Relaxation Movement in Frankfurt am Main. I meant to critique not art itself, but certain mechanisms functioning in the art world and the world focused on production. I suggested trying to change the perspective by opposing the pressure exerted by the (art) system. I invited viewers to join the Relax commune, all one needed to do was to get into a tourist car, listen to the sounds (my sister recorded her therapy session on Tibetan bowls), drink a tea of herbs that I brought from the Atlas Mountains in Morocco, get a hand massage with olive oil that I brought from the Pantelleria Island, get a clay face mask, or play chess. A few people just sat there for hours doing nothing.

-

Perhaps the pandemic has highlighted some tendencies more recently present in art. Although, given the interest in healing and care practices, it seems to me that the artists have actually predicted the pandemic.

-

-

Translation from the Polish

-

Joanna Figiel

-

-

-

-

Alicja Wysocka

-

Alicja is currently studying at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste — Städelschule in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. She studied at the Faculty of Cognitive Science and Philosophy of Mind at the Pontifical University in Kraków. She holds an MA in graphic design. Her work is situated at the intersection of art, design, and activism. In her work, Alicja deals with the topics of cooperatives, collaboration, alternative economies, as well as crafts, therapy, and rituals.

-