Amy Pekal

Compost and Other Means of Assembly

-

Think of the composition of a spiral, an ancient structure that frequently appears in nature, in shells and fiddleheads, in hurricanes and galaxies. Spirals help us notice the ongoing cycles of our individual and collective actions such as processes of composting – where lively matter organizes and transforms around non-linear timescales. During my residency at the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, I considered compost as a continuous prototype, an object that can be repeated and remade, one that is not fixed nor permanent. Through research, the process of composting both affirmed and continued the actions proposed by my collaboration with The Climate Justice Code (CJC), working group in which we continue to explore: How can artists and institutions care for our planetary commons with the power of imagination? 1

- Radical Radical imagination is defined as the ability to imagine the world, life and social institution’s not as they are but as they might otherwise be.2 For me, the compost process is both a metaphor and an artistic act that performs the radical imagination. It is the imagination rooted in ongoing social movements that ask us to draw on the past so that we can better understand why and how we can imagine the present differently. This radical imagination is something we do, it is a muscle rooted in praxis. A muscle that needs to be trained in order to become strong and capable. It is a matter of repetition with slight variation; stretching just a little further everyday. Radical imagination for our everyday lives requires a collective process.3 It requires willpower to cultivate and train the muscle, so that the ideas that come from thinking otherwise work for more beings.4 Radical imagination also asks us to develop new tools that help us decide where we are as beings, who we share the planet with and how to act differently. The tools I consider are not abstract, rather they are concrete gestures that are situated in community and embrace a practice of care.

- The compost bins help us to understand that cultural change to a more sustainable world is not made by policy or a dominant law alone, rather it is made through a plurality of arrangements situated in everyday practices between human and more-than-human collaborations. Composting as an act of maintenance engenders a collaborative process for human and more-than-human actors such as earthworms and microorganisms. Composting makes visible the supply chains and waste processes in everyday life and how decay is a necessary stage in fertilization and regeneration. Therefore, it matters how things decay. Compost leans into the need for a decay that is transformative, that generates new life, the type of decay that is necessary to build new worlds possible. How then, might we employ radical imagination to visualize and enact such decay?

- In the case of the compost bins on the grounds of the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, the project pulled unlikely collaborators together. The residents and residency department, the maintenance workers, administration, and realization departments as well as one of the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art's neighbors: The University of Warsaw Botanic Garden grew tangled into action. Mateusz Skłodowski, education and compost expert from the botanic garden offered to support the U–jazdowski compost experiment prior to constructing the bins by providing a consultation session to share his knowledge about the compost.

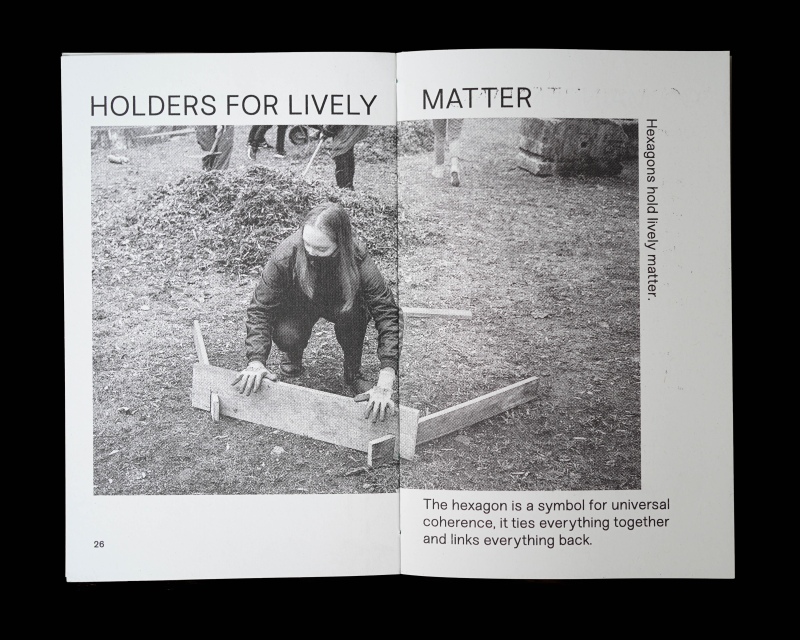

- The institutional assembly to build the compost bin took place on a mild and muddy spring day. This time of year, the area was sparse with little grass coverage and large acacia trees watching over us. The assembly was located alongside the institution, close to the pizza oven and recycling bins. Our group gathered on the grounds of the institution to co-create the compost bins. In a procession we pulled the building materials, benches, and tools from the laboratory and brought them to the site. When we arrived, we found a large heap contained the leaves and small twigs from around the institution’s grounds. Rather than driving the leaves away, the grounds men consolidated the surplus, and allocated it for the compost. .

- Once the site was prepared, everyone took a board and began to add their contribution to the hexagonal structures. As a participant in the process, I grabbed the wooden plank from the pile and passed it to empty hands. When there were no more planks in the reserve, we began to build. As I placed my plank to co-create this form, it felt as if time slowed down. The form spiraled upwards until a container emerged from our repetitive acts. To ensure that the compost bin would stay intact, the realization team supported our labor by fixing a few vertical beams to the structure. In a matter of minutes, the hexagonal forms stood upright. The compost bins were ready to transform surplus into humus.

-

- When the compost bins were completed, we entered the unknown of how to sustain and maintain our engagement with lively matter. The bins became a frame for transformative processes to emerge both in nature's cycles and through the institution’s commitment and care for more-than-human-worlds. One bin was designated to hold a reserve of carbon rich matter such as leaves, sticks and nutshells. While the other bin was fortified for the compost process to occur through alternating layers of carbon rich-leaves and nitrogen rich-biomass from food scraps and organic waste. Today, the bins foster the ongoing collaboration between the institution, visitors, and future residents. So long as the bins remain, they remind us of the better worlds possible.

- The lively matter in the bins invited conversations about maintenance and what comes after the initial start of a process. Afterall, maintenance is an ongoing and often overlooked form of labor. What did it mean to maintain a compost at the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art and how might the maintenance of a compost look like? It implicated those who maintain lively matter to the work of healing and restoring our relationship with the earth and considered it as not something that happens outside of civilization and communities but as part of the micro-practices of everyday acts towards life-affirming processes. Maintenance of the bins is a making-performing-thinking-praxis that is ongoing and unpolished but critical in the contribution to the revolution situated in the micro-practices of the everyday towards habitable worlds. Maintenance is also a communal effort; the health of the compost depends on the community that holds each other accountable in the care and nurturing of the lively matter.

- Compost as a tool for the radical imagination is situated in care, community, and the commons. Through composting we return the surplus of our organic waste to earth in order to regenerate soil and local environments. Compost is soil produced from garden or food scraps. The nutrient rich humus returns vital compounds back to the earth, enhances the capacity of the ground to retain moisture and encourages participation in life-giving and generative systems that support plants and other smaller organisms. Like compost, our work of healing and restoring our relationship with earth for generations to come is non-linear – it requires the coming together of multiple temporalities. When we compost, we imagine how future generations can learn from our acts to build generative relationships with the living systems that work ceaselessly to nourish and nurture our wellbeing. .

- To maintain and sustain the ecosystem of an art institution or other ecology requires ongoing and repetitive acts. Thus, as a continuous prototype, the compost bins gesture towards imagining how the world could otherwise be when one practices a vision that embeds relations of care and respect into the maintenance work that sustains everyday life.5 The more our cultures choose to compost the more it becomes the dominant narrative of our relationship with nature. However, even as I argue for all the goodness a compost can bring towards changing culture, I still approach the question of my work with criticality, particularly when I ask: what does composting have to do with an art institution’s agenda? The conditions of which I locate agency as an artist are bound by the temporal constraints of a three-month residency. To me, the bin represents the need for more ideas in more places that can be enacted by many hands to practice the antidotes to the present dominant climate narrative. Therefore, the prototype can be cared for and by others but the duration for which the care is carried out reflects the value institution places on such processes.

- The dominant Western cultural narrative around climate resonates as urgent because extractive tendencies, industrialization and development have accelerated the frequency of erratic climate conditions. According to María Puig de la Bellacasa, the temporal pace required by soil’s ecological care as a slow renewable resource might be at odds with Western culture’s conditions of emergency. These conditions are often paired with the accelerated linear characteristic of technoscientific futuristic responses.6 In the West, we know urgencies, the statistics and calculable graphs but do we know soil? Erosion is one of the many matters calling for global environmental care, specifically the global exhaustion of fertile land. But my concerns with soil are less about the science behind fertile humus and more about the social relationships that emerge from our engagements with lively matter on a 1 to 1 scale. Through mundane and everyday activities, we just might reorient our sensibility towards the living world. Thus, when I feed the compost, my acts constitute a pattern – a habit and I recognize that the knowledge produced here is situated and tethered to the context of this micro-practice. The compost bin becomes the infrastructure for more-than human assemblies to transform with time.

-

-

-

- To compost is to take a risk, to make something that might fail. It is an opportunity to learn that maintenance of the compost forms concrete practices of climate-just worlds and enacts some small semblance of care towards an ecological sense of well-being. When we compost, we prioritize relation, praxis and complexity as key components that begin from the here and now to actualize and construct potential futures. We open ourselves up to the possibilities of going deeper, being more empathetic and more vulnerable in human and more-than-human engagements. We learn how to both embody and enact a life-affirming ethics through ongoing micro-practices and situated engagements. When we no longer not rush to transform something that needs ample time, then our efforts produce fertile ground..

-

Iwant to return to my initial investigation that prompted how artists and institutions could come together to combat the climate crisis with the power of imagination. This micro-practice to return the surplus of organic matter is one of many ways we lean into the worlds we want to see every day. Through a democratic process we built compost bins for the institution, looked towards our neighbors to help us understand the science of composting and extended the invitation to the institution to contribute to the composting process. .

- Perhaps with all these knowledges, we can better see the multitude of relations that make the worlds we think with. The work of healing and restoring our relationship with earth for generations to come is the work of assembling kinship networks that radically reimagine our relationship to lively matter in capacities big and small. Organic process contain an enormous amount of complexity that is impossible to be broken down and distilled into categorically separate entities.

-

- Amy Pekal

- 1 The Climate Justice Code (CJC) is an initiative that originated at Our House is on Fire the second annual Assembly for Commoning Art Institutions organised by Casco Art Institute: Working for the Commons and led by a steering committee and editorial committee. In the two-day Assembly this question was posed to guide a collective drafting and editing of a Climate Justice Code for artists and art institutions. Out of the initial two-day gathering a working group was formed which meets regularly to continue its work on the code.

- 2 Max Haiven and Alex Khasnabish, The Radical Imagination: Social Movement Research in the Age of Austerity, (London: Zed Books, 2014), 10.

- 3 Haiven and Khasnabish, The Radical Imagination, 10.

- 4 adrienne marie brown, Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds, (Chico California: AK Press, 2017), 60.

- 5 María Puig de la Bellacasa. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More Than Human Worlds (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2017),170.

- 6 Puig de la Bellacasa. Matters of Care, 171.

- 7 Rosi Braidotti,”Nomadic Ethics” Deleuze Studies 7.3 (2013): 343, Edinburgh University Press doi: 10.3366/dls. 2013.0116.

-

Bibliography

-

Braidotti, Rosi. ”Nomadic Ethics.” Deleuze Studies 7.3 (2013): 343-359. Edinburgh University Press. https://doi.org/10.3366/dls.2013.0116.

-

brown, adrienne maree. Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds. Chico California: AK Press, 2017.

-

Haiven Max, and Alex Khasnabish. The Radical Imagination: Social Movement Research in the Age of Austerity. London: Zed Books, 2014.

-

Puig de la Bellacasa, María. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More Than Human Worlds. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

-

-

-

Thank you to

-

Marianna Dobkowska, Katarzyna Sztarbała, Nela Szadkowska, Marta Grott, Paweł Słowik, the Administration and Economic Department and the Technical Department of Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, Mateusz Skłodowski, Nadia Elamly, Fleur Roggeman, Aleksandra Biedka, Julia Harasimowicz, Ika Sienkiewicz-Nowacka, Binna Choi and the Climate Justice Code working group.

-

-

-

Curetor of the project and Amy Pekal residency

-

Marianna Dobkowska

-

-

-

Production

-

Katarzyna Sztarbała i Nela Szadkowska

-

-

-

Consultations and support

-

University of Warsaw Botanic Garden

-