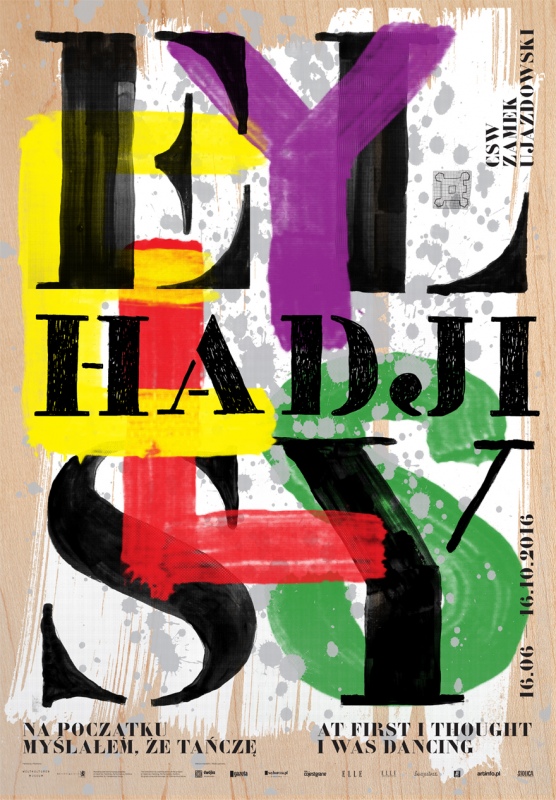

16/06—16/10/2016

exhibition

El Hadji Sy

At first I thought I was dancing

-

The Choreography of Community

- “At first I thought this was dancing. Then I realized that I wasn’t dancing but kicking. After that experience, kicking became an instrument within a general economy of composition. My foot became the brush with which to paint a systematisation of the trace of the body. […]Instead of saying that I paint, I prefer to say that I enter into the painting. [...] The Western concept of painting revolves around the hand-eye concept. I wanted to kick out this tradition like a football, with one violent gesture." (1)

- The exhibition of El Hadji Sy will constitute the first presentation of the Senegalese artist, curator and activist in Poland. Born in 1954 in Dakar, the artist is one of the key figures of the art scene in West Africa after it gained independence. Since the 70s, he has been proposing pioneering and interdisciplinary models of action, under which he tests the field of art and possible ways of utilizing it. His numerous activities always seemed to balance between belonging and escaping, whose subject could both be the postcolonial heritage of Senegal, the ideology of negritude (2), as well as local traditions, global markets and, in the end, any systems, including those internally governing art.

- Senegal gained independence in 1960, after almost two hundred years of French colonial rule, which deemed the area around today’s Dakar - Gorée Island - the main centre of the African slave trade. The first president of free Senegal, Léopold Sédar Senghor, was a scholar, poet, and philosopher, well-educated at the University of Paris, and the first African who became a member of the French Academy. He held the position of president for twenty years, until 1980, when he retired from politics. For two decades he worked on creating an outline for the new nation - based on structures that are democratic, modern, and supporting the development of education as well as culture. The identity of the young nation was built in tension due to the continuing and import of French patterns and the Pan-African ideology as well as negritude, whose ideas were supported and co-founded by President Senghor. Serving the government after him was Abdou Diouf, who based the development of the nation on a technocratic model, in which he marginalized and limited the role of culture.

- The forming map of political, ideological, economic, and social relations, under whose frames the new Senegalese identity was developing, as well as developmental dynamics, modernization and changes in the metropolis, which Dakar was becoming, defined the benchmarks for the methods of operation of El Hadji Sy and artistic groups with which he was associated (3). El Sy painted by kicking the canvas, stomping on it, in order to "kick out" the colonial, western cultural tradition. That gesture of kicking has become a characteristic signature of the artist. The radical negation was supposed to emphatically define the artist’s positive proposal. He initiated a number of artistic groups, often fusing painters, poets, people of theatre and experimental cinema, as well as intellectuals searching for hidden correspondences between the different mediums and a new language of art. He organized music festivals and participated in radical theatrical experiments. Although he enjoyed the support and admiration of President Senghor, the artist was able to openly protest against the cultural policy of the nation, creating along with other artists their own, grassroots initiatives and structures. Even though his paintings were valued and presented on the international scene since the late 70s, he was able to boycott the prestigious events to which he was invited to partake in (e.g. he refused to take part in the famous exhibition organized by the Centre Pomidou, Magiciens de la Terre in 1989 and in the program of the biennale in Dakar in 1992, in which he took part prior in several editions; in protest, he exhibited his works on the street). For years he was developing, along with the members of collectives that he co-founded, ephemeral events based on mutual relationships as well as relationships with local communities. At the same time, together with the German linguist and art patron Friedrich Axt, he gathered in the 80s for the Weltkulturen Museum in Frankfurt a pioneering collection of Senegalese contemporary art and published the first anthology on the Senegalese art scene. In the mid-90s, together with Clementine Deliss, he prepared the exhibition Seven Stories about Modern Art in Africa, in which he also partook, in the White Chapell Gallery in London and the Swedish Malmö Konsthall. In 1997 he participated with Clémentine Deliss in documenta 10 in Kassel, where as a part of the program 100 Days - 100 Guests they presented their magazine "Metronome," and for the next edition of documenta (2002) the group Huit Facettes, which was co-created by him, was invited. In 2015 he was invited to a presentation within the frames of the Biennale in São Paulo. In response to a question about the assessment of the contemporary art situation in Senegal, he says that no matter where on the globe, "art always has the same problems: to propose models, distribute and introduce them into international critique."(4)

- The exhibition at the Ujazdowski Castle wants to look at these particular models proposed by the artist, a specific cultural experience, the frames in which they arose as well as the possibility of their universalization. Over 100 paintings (including several works of Senegalese artists selected for the exhibition by the artist), objects, posters, and documentation (archival records of performances, photographs, manifestos, the magazine "Metronome"), as well as a performance created especially for the exhibition will help investigate the models of performativity and processuality proposed by El Hadji Sy and the surprising place in which the body, object as well as the global flow of people, goods and meanings are found within its frames. “A finished object as such does not interest me. It’s the process that fascinates me." - says El Hadji Sy (5). The performative process and its particular choreography obviously imply the emergence of an object at some point. However, the role of the object, image, or installation is actually subordinate to some degree to the process itself. It is the process with its hidden musical, rhythmic structure that strongly transforms and bends reality. In some ways it embraces objects in its possession to - with the trend expanded by them - flow further in the direction of the community, and to test the limits of its causativeness.

- El Hadji Sy points out that "the tradition of creating art in Africa is something communal. When you make something, the community is involved in this process. It’s the community that accepts it. A work of art becomes a social object, extended and embellished by the community. And it finds its reflection in it." (6) The artist co-founded several collectives. The first of these was the Laboratoire AGIT'ART, which since the 70s, for three decades, conducted a radical exploration on the borderlands of theatre and visual arts, combining performative actions with social ideas. The figure who sponsored numerous actions of the Laboratoire was Georgi Plekhanov - creator of the social-democratic movement in nineteenth-century Russia and a political émigré. In the beginning the group was associated with the experimental theatre Les Tréteaux, which acted in opposition to the national stage of Dakar. Its members, including El Hadji Sy, also established a relationship with the Psychiatric Clinic at the University of Dakar, whose director Henri Collomb remained impressed by the traditional African methods of treating mental illness. They assumed the full inclusion of the patient in the daily life of the local community as well as the inclusion of the therapist in the daily life of the patient - in contrast to the European practice of isolation. Under the influence of his visits to traditional Senegalese hospitals, Doctor Collomb abolished hierarchical divisions between the patients, staff, and physicians, and included healthy family members in the treatment process of the patient. Contact with experimental psychiatry and a reference to the traditional rituals was not without influence on the performative actions of Laboratoire AGIT'ART and on the tensions accompanying them between that which is individual and that which is communal.

- In the early 80's, El Hadji Sy initiated a space for international projects and workshops of artists from various fields - Tenq.7 The goal of these workshops were meetings: first between artists, in which the process of their joint work and its dynamics played a crucial role, followed by a final meeting between artists and the public. In 1996, along with seven artists he co-founded the group Huit Facettes (8), which not only exhibited together, but also, among other activities, conducted workshops with the residents of Senegalese villages, together changing the local economic, social, and cultural conditions of their functioning. In the village of Hamdallaye, the structural changes developed by artists and locals have survived to this day (9). The site of action, both for Tenq and Laboratoire AGIT'ART, was the Village des Artes - a kind of "town" of artists, created by them, independent of government assistance, and even in opposition to it (10). Unused postcolonial military barracks became a place of experimental work for about seventy artists representing various fields and conducting in them studios and workshops. In 1983, the artists were made to leave, and the Village was destroyed by the army. It was, however, arranged again 13 years later, in an abandoned settlement for Chinese construction workers in Dakar, where the Village des Arts operates till this day and where El Hadji Sy has his studio.

- Within the frames of the activities of all these groups, as well as more or less transient communities, an art exhibition was not the only and not necessarily the most important element. Sometimes it did not happen at all, and sometimes it may have seemed that the exposition was a side effect of complex and sophisticated processes: performances, formal and informal discussions, meetings with the public, workshops, think tanks, and work (as part of the activity of Laboratoire AGIT'ART) on the publication of successive issues of the magazine "Metronome." (11) The most important for these groups and for El Sy was the "mobility of art," the process of testing, transformation and change, which does not necessarily have to have a calculated finish, but rather resulting from the dynamics of the process itself.

- The basic criteria developed by European dictionaries for contemporary art, such as painting, performance, object, despite so many turning points in modern and recent history of art that undermined it, seems to refer to the practice of El Hadji Sy as something strangely awkward, disparate, or simply untrue. The artist does not say that he paints, but that he "enters into the painting," (12) which has its entrance and exit. He has been literally walking on the canvases of his paintings since 1975, stepping on and kicking them. “At first I thought this was dancing. Then I realized that I wasn’t dancing but kicking." (13) Through this gesture, he not only rejected the figurative canon in the visual arts, imported from France by President Senghor and promoted at the time by Ecole de Dakar, but he rejected the entire Western tradition of painting, which is based on the intellectual relationship between the "hand-eye," while the most natural cultural form of expression in Senegal is more connected to dance, movement, and singing. In this way, the gesture of kicking has become an important part of the overall economic activity of El Hadji Sy and a systematic record of the traces of the human body. The viewer’s body is also of great importance. The manner in which the paintings are displayed – objects suspended in space, kites hanging over the heads of the viewers, canvases spread out on the floor, or vertical movable structures – impose a specific choreography on the viewers, who are forced to move their eyes and body, thus unconsciously becoming part of the performance, into which the exhibition transforms. In the 70s and 80s, painting - physical or in the form of a projection projected onto the artist's body - was also part of the performances constituting parts of the artist’s exhibitions.

- A crucial part of the processes initiated by El Hadji Sy is the material. He paints on, e.g. empty bags of rice or coffee, on the paper used in butcher shops or on the silk intended for kite production. El Sy explains: "I do not like the idea of a perfect white canvas with a smooth surface. For me, the surface must be like skin - physicality with which I can work, which is changing."(14) The surface seems to indicate the organicity of the painting, its biological ties with the outside world, from which the processes grow. The choice of material is therefore essential. And so the empty bags of rice, which is a massively imported product to Senegal and the fundamental source of food for the working class, are collected by the artist by knocking on the doors of private homes. He then later sewed them together into a canvas 2 to 3 meters in size and painted, selling the converted material back to the owners for the price of a bag of rice. (15) In this way, the movement of goods, Asian-African trade routes, and economic relations undergo an essential transformation. The basis of the installation Archeologie Marine, implemented at the Biennale in São Paulo, were in turn fishing nets, thanks to which the artist made the titled marine archeology: fishing out millions of slaves’ bodies lying on the bottom of the ocean from oblivion, transported in the seventeenth and eighteenth century from the area which is known today as Senegal to Brazil. Every object, every material, according to the artist, contains all the affairs of this world - like in the story "El Aleph" from Jorge Luis Borges (16). The artist is the one who gives life to the material; he follows the circulation of objects, goods, people, forgotten meanings as well as history and combines them into a network of biological connections.

- Searching for new, organic relationships between the body, world, objects and materials as well as translating them into the language of artistic activity is part of the process that El Hadji Sy calls the "visual syntax." He defines his method as a transformation of experience into paintings through the use of his own body. It acts as a kind of transformer, strongly transfiguring the grammar he utilizes, also the visual syntax, which results in an effect reminiscent of the linguistic principle of poetry. Poetry, which - according to Franco Berardi - is the way of salvation in a world automated by the dictates of modern world economy; by way of the language of excess, through which we can recover the emotional body and its singularity, and thus the realm of meaning and sensuality in social communication (17).

- Małgorzata Ludwisiak

- (1) The Artwork becomes a Socialised Object, Enhanced and Embelishesd by the Community. El Hadji Sy in Conversation with Julia Grosse, [in] El Hadji Sy. Painting, Performance, Politics, ed. C. Deliss, Y. Mutumba, Weltkulturen Museum, Frankfurt 2015, p. 47 and 46.

- (2) Negritude, literally "negroness," is a movement that began in the 30s in France by black intellectuals, poets, and politicians, including the future president of Senegal Léopold Sédar Senghor. The main principle of the movement was to seek the value of the history and cultural heritage of the indigenous people of Africa.

- (3) Cf.: Contemporary African Art, S. Littlefield Kasfir, Thames and Hudson, London, 2000, p. 124-126, 166-174; M. Diouf El Hadji Sy and the quest or a post-negritude aesthetics, [in] El Hadji Sy..., op. cit., p. 134-140.

- (4) El Hadji Sy in Conversation with Hans Belting, [in] El Hadji Sy ..., op. cit., p. 304.

- (5) El Hadji Sy in an interview with Antje Majewski, The Stone, The Ball, The Eyes. Conversation with El Hadji Sy, video 26,01 min., 2010.

- (6) The Artwork becomes a Socialised Object…, [in:] El Hadji Sy..., op. cit., p. 45.

- (7) The word Tenq in the Wolof language means "ankle" or - more broadly – a place that connects. Cf .: C. Deliss, Brothers in Arms ..., p. 188.

- (8) Definition: Eight Facets. The original name of the group was Huit Facettes Interaction.

- (9) Cf.: Exit the aquarium. El Hadji Sy in conversation with Małgorzata Ludwisiak, [in] El Hadji Sy. At first I thought I was dancing, exhibition guide, ed. M. Ludwisiak, K. Marcinkowska, O. Byrska, Warszawa 2016, p. 24-27.

- (10) President Senghor promised the creation of Cite des Arts, the City of Artists - infrastructure in Dakar was dedicated fully for the benefit of art institutions and a studio for artists. The dilatory actions of the government in this regard provoked the artists to undertake independent, grassroots activities and critical commentary in the form of changing the titled city (cite) to village (village).

- (11) Cf. C. Deliss, Brothers in Arms…, p. 188.

- (12) Cf. The Artwork becomes a Socialised Object…, p. 46.

- (13) The Artwork becomes a Socialised Object…, p. 47.

- (14) Ibid., p. 42.

- (15) C. Deliss, Brothers in Arms…, p. 190.

- (16) Cf. El Hadji Sy in an interview with Antje Majewski, The Stone…

- (17) Cf. ”Bifo” Berardi, The Upraising. On Poetry and Finance, MIT Press Cambridge-London, 2012, p. 20-22.

Today at U–jazdowski