Róża Duda and Michał Soja

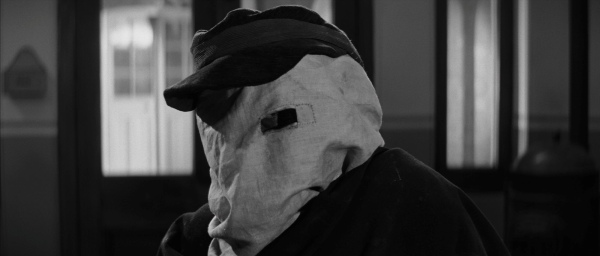

Never Embrace Burning Statues

The story of Faustin Wirkus, a Polish American coal miner, warrant officer in the US Marine Corps, and king of the Haitian island of La Gonâve, has never been adapted for film yet. In their reconstruction of the man’s history, Róża Duda and Michał Soja blend fact with fiction and conjecture, speculating on the biography of Wirkus, who thinks back to his participation in the occupation of Haiti by the United States.

Duda and Soja undertake a psychoanalysis of a culture bridled by rationality. This they do in a convention of high adventure. The location – the sunburnt island of La Gonâve – seems a perfect backdrop for that.

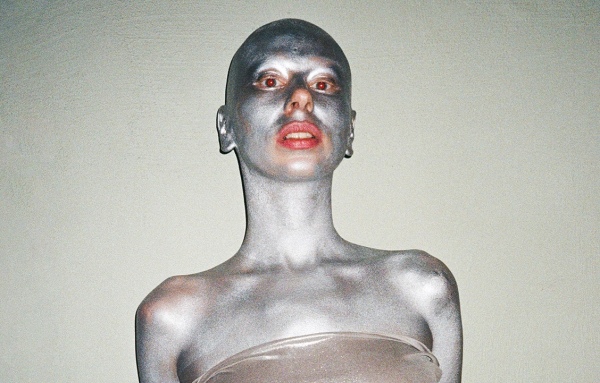

In trickles of sweat running down hot skin and in sultry air filled with the buzzing of insects and putrid fumes oozed by the humid jungle, the protagonist experiences a need of rebirth.

We follow the final episode of Faustin’s stay on the island of La Gonâve, the moment when he notices that the logic of plan and productivity he professes has become exhausted. The civilization that he has left behind, populated by listless automata, deprived of agency, will, and creativity, harnessed to the treadmill of their jobs, begins to lose its contours.

Dark, throbbing with fresh juices, the jungle melds forms. Its vivacity exposes the exhaustion of a culture based on the separation of individual beings, permitting a carnivalesque abolition of hierarchies, privileges, norms, and prohibitions.

Turbines working at full speed, engines whirring irregularly, oils and greases flowing, all herald the collapse of established order. Whether because of the sweltering heat or because of voodoo rituals, matter itself seems more fluid and flexible to Faustin. Swollen veins heat up like the cables of a machine in overdrive. The body slips out of control, like a lump of melting fat, going limp and yielding to the rhythmic sounds which awaken in him dormant desires of transformation and revival. Worn forms must perish in purifying fire, making room for new ones.

Faustin appears here as a pars pro toto of Western culture, an everyman who, influenced by an encounter with the other, transgresses narrow horizons shaped by toilsome mine work and military drill. He wants to see himself as a romantic rebel, a saviour, a revolutionary. He disarms the system in his visions, instigating us to revolt against reality, to overthrow entrenched rules, to risk rebellion with all its consequences.

- Text

- Marta Lisok