When danger becomes fun

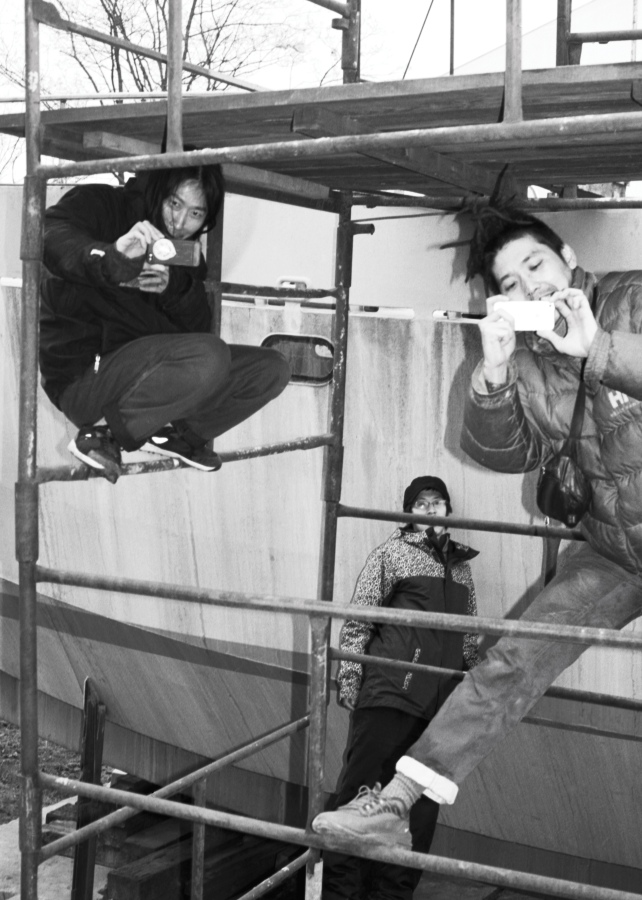

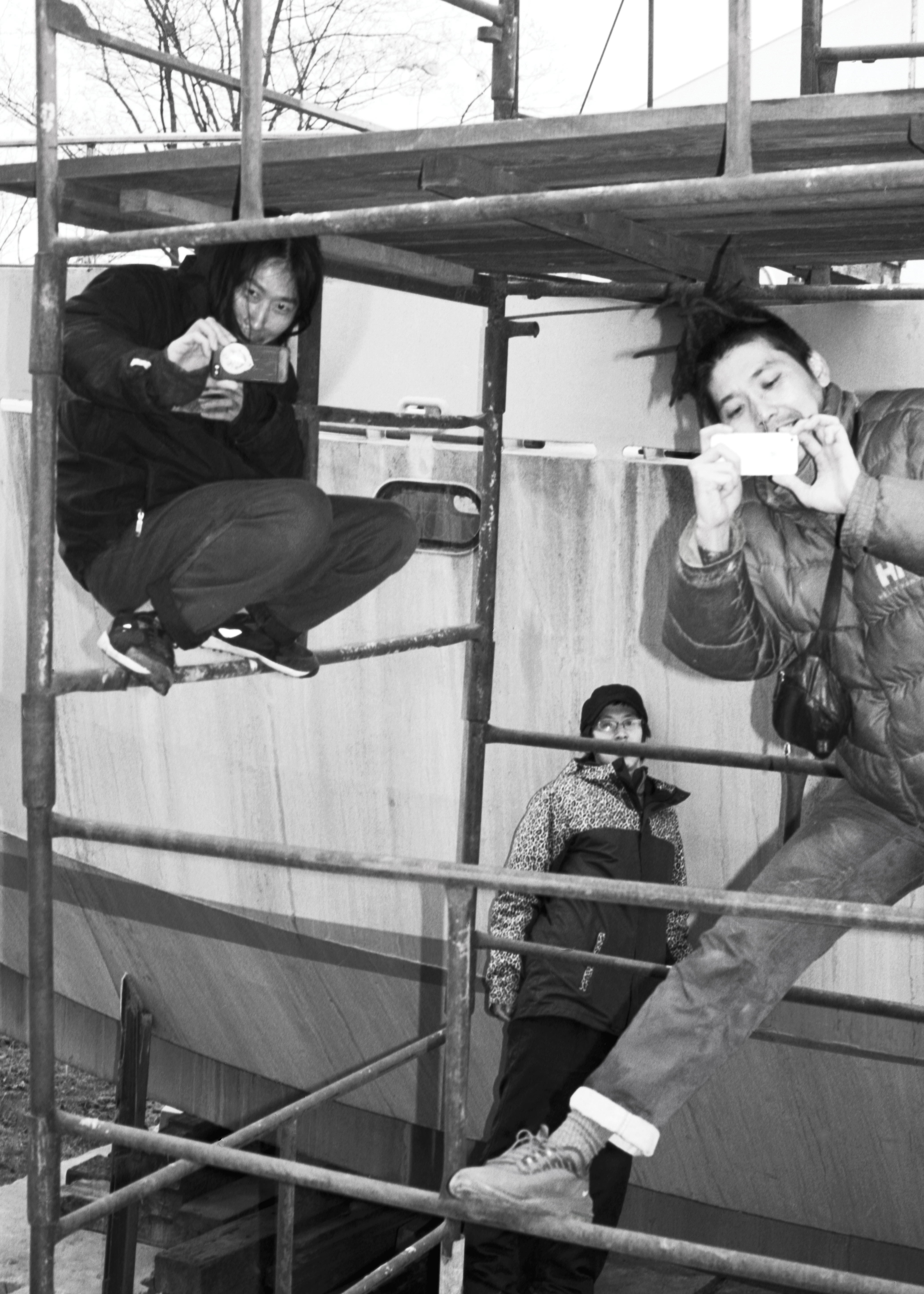

Itaru Kato, Fuminori Hoshino, and Yuu Yoshida of the hyslom collective tell Agnieszka Sural about the Japanese art scene, the field play method, stones and pigeons, but also about risk-taking and testing limits.

-

Agnieszka Sural: This year marks the tenth anniversary of hyslom. How did it start?

- Itaru Kato: We met at the Kyoto University of Arts, where I studied Textile Design, while Fuminori and Yuu were doing an Architecture course. After graduation, we all went back home. We are from different towns. One day I saw through a window of my parents’ house that a mountain which used to stand there had disappeared. Instead, there was a fence and an announcement about an upcoming residential district. This was in 2009. We entered the construction site on a Sunday, this being the only day no work was going on there. The first thing we saw was a huge pile of trees that had been felled there. We returned there every Sunday for the next ten years, and each time the landscape was different. Our collective was formed, but we didn’t think about it like we were doing an art project for an exhibition. It was just field play, and using the opportunity to shoot videos and take pictures.

-

What does hyslom mean?

- Fuminori Hoshino: We published the photos and videos taken during the weekly field plays on the website hanareproject.net, which is run by the Kyoto-based Social Kitchen. Then the need arose for a name. We called those practices on the mountain “Documentation of Hysteresis.” Hysteresis is the dependence of the state of a system on its history. When you stretch a piece of rubber and let it go, it contracts and returns, but not to the same position. That’s how we imagined our practices on the mountain, where things were constantly changing and were never like before. The collective’s name is a compound of “hysteresis” and “slalom”. The natural conditions of the mountain are slopes and cliffs, which we circumvented slalom-like.

-

hyslom

hyslom

Photo: Dawid Misiorny

-

How do you collaborate?

- Yuu Yoshida: At the beginning we didn’t think about our joint practices as work, we did it spontaneously and for fun. When different people had started inviting us to exhibitions and paying us for it, the term “deadline” came into play. The deadline by which you need to think over and decide everything, and even to organize or fix something. This was no longer just fun. So the conditions to which we have to adapt have changed.

- Itaru Kato: What is important for us is to share everything. We take care of everything together. There are no assigned roles like in a music band, where one person writes the lyrics, another composes the music, and a third one sings. Even if such task-delegation would save us time, it is more important to experience together.

-

You call your artistic method field play.

- Fuminori Hoshino: Play not in the literal sense, but as a neologism. Anthropologists have field work, and we do field play through art practice. There are no rules, so it’s not a game. It’s about going outside and playing.

- Yuu Yoshida: The word play relates also to the 1980s Osaka collective Play. Its members organized all kinds of outdoor events. They built a wooden structure on a hill and waited for a lightning to strike it. They found some road signs, made them into a raft, and rafted down a river. Hyslom differs from them insofar that we improvise, operate ad hoc, in response to a situation encountered in nature. We don’t preplan our actions.

-

What does play mean to you?

- Itaru Kato: Play involves pleasure and a suffering effort. It is a response and reaction to a new situation, a push beyond your limits. One time we went out during a typhoon. A storm was raging. You could hardly stand and breathe. In such situations you get to know your own body. If there are three of you, you get to know them closer. If you hold hands, it’s easier to resist the wind. In a trio, even tough, painful, or dangerous experiences become nice. When you share risk, danger becomes fun.

-

What did you do while in residence in Warsaw?

- Yuu Yoshida: When we came here for the first time in 2016, some artists from Indonesia were also in residence. We spent time together and took part in the programme organized by the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art curators. We were shown various places, such as the tractor factory in Ursus. Nearby we found a ship that, as it turned out, was being built by homeless people from a nearby shelter. We got to know the construction manager and future captain of “Father Bogusław”, Mr. Waldemar Rzeźnicki. We learned that in the following year, when the ship would be finished, its builders intended to use it to sail around the world. Then we decided that we’d return to Ursus.

-

I’ve heard you got employed there.

- Yuu Yoshida : We asked the ship captain, if we could help and he said yes. Together with homeless people and master shipbuilders, we were building “Father Bogusław.” We worked for two weeks, every day from nine to five. None of us spoke English, but we communicated through gestures and learned each other’s languages.

- Itaru Kato: The captain from Ursus helped us find a cheap boat that we later used to travel down from Warsaw to Gdańsk. We already had motor boat’s licences, having done projects on rivers in Osaka and Nagoya. We sailed for two weeks, making stops at various places. We documented all our activities, marking the places visited and routes covered on a map.

- Fuminori Hoshino: In the meantime, we had taken part in an exhibition at the Nikolaj Kunsthal in Copenhagen, which featured another Japanese artist, Yukawa Nakayasu. One of the elements of his installation was a large stone. When we saw that, we felt nostalgia. We’d once found a similar stone in a river in Kyoto and used it in our performances. We brought it back every time, but two years later it disappeared. The river had carried it away or someone had taken it. It was so large the three of us could barely lift it.

-

-

Then you decided that one day you’d take the Copenhagen stone with you.

- Itaru Kato: We looked at the map and saw that we could get to the Vistula by sea. When the captain heard about our plans for the stone, he organized a crew, a yacht, and we sailed from Gdańsk to Copenhagen and back.

- hyslom

Photo: Dawid Misiorny -

Itte-Kaette. Back and Forth is the title of your show at the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, opening in December 2019. What does its first part – Itte-Kaette exactly mean?

- Yuu Yoshida: In Japanese, itte-kaette is a connective construction where a second verb defines the tense of the first. It’s a construction which means that someone has gone and come back. Or to go and come back. Literally, itte is outside, kaette inside. For us, this is immanent repetition. We’ve recently been travelling a lot on various routes, and the repetitiveness of these motions inspired the title. It made our curator, Anna Ptak, think of Albert Camus’s The Myth of Sisyphus. At some point, I felt a shift in the centre of gravity that is marked as home on the mental map. I return home to Warsaw and leave Japan. It turns out that various places can be your home. This situation can be compared with the work of Sisyphus. It’s hard work, but with a shifted centre of gravity the goal is not to roll the boulder up, but to let it roll down.

-

What are you planning for the show?

- Itaru Kato: Before the trip for the stone, we are participating in the exhibitions Celebrations in Poznań and Szczecin, devoted to the centenary of Polish-Japanese diplomatic relations. We’ll present performances there and show a few objects related to the stone. We’ll create a space where we’ll be able to receive it. In Warsaw, the exhibition will be based on our meetings with various people, a documentation of encounters with the landscape, with animals, and the stone trip. We will work physically with the stone.

- Yuu Yoshida: We also want to show works from our ten years’ practice. All our projects are somehow connected. Now we’ve found a stone we interact with, like we used to explore that construction site. It’s about becoming familiar with matter, interacting with it.

-

What will happen to the stone next?

- Itaru Kato: The show concludes in March 2020. At this time the water level on the Vistula should be high enough for us to be able to sail to Gdańsk. If the timing is right. From there we’d perhaps like to take it to Sapporo, where we’re doing our next project.

-

Working with racing pigeons has been one of your long-term projects. Will birds feature in the Ujazdowski Castle exhibition?

- Itaru Kato: At the Castle we met the cleaner, Mr. Mariusz, and his pigeons. We meet regularly. The plan for the trip is to build a dovecote and take it along. On the way to Copenhagen and back we’ll be stopping by and borrowing pigeons to release them after two hundred yards. It’s interesting that pigeons swallow stones to aid digestion.

-

-

What’s the attitude towards pigeons in Japan?

- Yuu Yoshida: Ordinary pigeons are dirty, disgusting, but racing pigeons are different. They are nice to touch, they have different eyes.

-

You spoke about deadlines. Mankind is also facing one. Various experts give us nine, twelve or thirty years. How does hyslom see itself in a decade from now?

- Yuu Yoshida: What I wish for are closer relations, less distance, and more dialogue. Not only within the collective, but among people in general.

- Translated by

- Sara Manasterska

Marcin Wawrzyńczak

- Sara Manasterska