Embodied research and collective knowledge

Rémi Dufay in conversation with Klara Czerniewska-Andryszczyk

-

How did you end up at the U–jazdowski residency?

- I met Julia Harasimowicz when she visited my studio in Geneva. It was funny because initially she didn’t tell me why she was there; she just said she was visiting some artists. Two weeks later she emailed me and invited me to the Empathic Pedagogies seminar, and to a residency at the Ujazdowski Castle. Everything was already prepared with the Pro Helvetia foundation.

-

Had you been on residencies before?

- I was in Uruguay for a month last December. It was quite intense because I had two weeks of work and one week for a presentation at a festival. We made a film in two weeks! I am also an associate artist at L'Abri, a residency for young artists in Geneva.

-

Before lockdown, did you have a chance to discover the local art scene?

- A little bit. It does feel strange to be here during lockdown, but it’s also nice because I am here together with other artists.

-

Can you tell me more about Empathic Pedagogies – were you invited because you were engaged in education beforehand?

- I don’t know if I am the best person to talk to about this because I only did two weeks of it. Due to Covid, the seminar was run in a totally different form – online. It was nice to be part of a group and to discuss what happened during the pandemic, but for me, establishing a new relationship over Zoom at a time when a good part of my professional and social life was taking place in front of a screen was too much.

-

How did the pandemic affect your calendar this year?

- That’s a huge question. I am an artist, but I also work as an organiser and coordinator of artistic events. Together with Benoît Beurret, Fabien Duperrex, Charlotte Magnin, and Kevin Ramseier, I am in charge of the BIG biennale in Geneva (Biennale Insulaire des Espaces d’Art de Geneve – bigbiennale.ch). We started to work on the 2021 edition in January of this year and then the first lockdown was announced. Back then, we needed to write out all the texts and come up with the concept of the biennale. I had a hard time working on it, a full year and a half in advance, not knowing what would happen in the near future with all the urgent political matters going on in my home country of France: the implementation of liberticidal measures, delirious police repression, etc. There was a strong urgency to do something, to act now, and so the idea of working on a distant artistic biennale seemed completely out of place. After a long discussion within the team, we decided it was important to maintain the biennale as a source of joy, experimentation, reflection, and encounters, but on the condition that we use our status to improve things in the cultural landscape of Geneva. With the hope that if everyone acts from where they have power, we contribute to moving towards massive societal change. We wanted to focus on sharing, building a community, on using existing resources, but we did not want to fall into the trap of empty discourse and void actions, which is unfortunately the hallmark of many art institutions and festivals today. So we decided to take very specific steps. For example, we simply wouldn’t sound credible if we continued to work with our sponsor, i.e. the Loterie Romande [Francophone Swiss Lottery Fund], a company whose business model is based on the idea that you’ll be rich if all others fail. We also stopped asking for money from private foundations and decided to erase selection, which I personally find problematic in an artistic milieu that is mostly left-wing.

-

What do you mean?

- This means we will accept all the projects we receive: the only condition for participation is to be an art space or a Geneva-based collective. The point of all this is to create a precedent, to say: look, we refused private subsidies, we refused to be selective, we refused to be profitable, and we still managed to create an edition even more beautiful and crazy than the previous ones. So you see, it is possible!

-

Do you think private sponsors have too great an impact on the content of the festival?

- That’s not the point. We’re not against private funds, we don’t say if it’s good or bad. We just want to try to do it a different way, because very few structures do that – we have this opportunity because we are a little biennale. In Geneva, 99% of the art spaces and artistic projects are funded by both public and private donations from various foundations; very few people think they could go without those private funds. With the biennale, we wanted to escape it, to question it.

-

Why did you choose to move from France to Geneva?

- I had an impression that I only started to understand what is important for me in an art school during my MFA in France. I wanted to learn more, and I wanted to go to another place just to see what would happen. I deeply believe in ‘aller-retour’, because if you go to another place, you get to understand your own context better.

-

Can you tell me more about your art – do you feel connected to theatre rather than to the visual arts?

- I have always been quite close to the theatre in my artistic practice, but it intensified when I started a residency at L’Abri. There, I was given a bit of money, a lot of space and help, and could do research on whatever I wanted. I did a project called D’Amour et D’Eau Fraîche, a travelling play. The title is a French expression meaning that if you’re an artist, for example, you live on passion alone, without money – only on your love for what you do, and on fresh water. This was my first big project; I had to create a team, ask for funds, engage actors – for me it was massive. The plot of the play revolves round a theatre director who, on the day of his premiere in a theatre outside Geneva, and lost amid ethical questions, decided not to play the show to his audience, but to offer them something else instead – to go to the seaside. The play was shown as part of the festival, La Bâtie, in September 2019. For me, it was a way of modelling and conceptualising my research about funding (being funded), and a theory I developed while at L’Abri, called l’affaissement – a geological term that can be translated as slumping, sagging under pressure or weight – which is to say that you stop fighting for your political ideals and try to protect the privileges you have gained already. It is a fear that I feel strongly in Geneva.

-

Can you tell me more about the development of l’affaissement?

- While on residency at L’Abri in the autumn of 2018, I decided to make a film, a large shoot at L’Abri – six cameras and 25 microphones everywhere around the space. It was a huge installation in which we lived for three weeks, inviting some forty different people to discuss the concept. It was a collective discussion – I wanted to carry out live research instead of thinking about it alone. I also decided to work on the context of the discussion – while shooting the participants, I invited some performers to play music, dance, or even cook dinner, which had an impact on what the participants were saying. I also developed a technique I called interposed bodies (corps interposés), which used a system of screens and microphones to allow one person to speak to someone through the body of another. It turned out to be a very powerful tool.

-

Was this film and installation ever shown, or was it only part of your visual research on the topic?

- I wanted to hold an exhibition with all the materials from L’Abri, but it was in November 2018, and one month later I learned that I had been selected to carry out the D’amour et d’eau fraîche project. I had just eight months to do it and it was a very large project for me that I had to focus on totally. However, through this research on l’affaissement, I managed to create the characters for D’amour et d’eau fraîche. The project at L’Abri is a good example of how I work: I try to do research, but through concrete stuff like film, and then turn that into other forms, such as a theatre piece.

-

Are you also a performer? Do you perform in your films?

- Yes, I did 10 years of theatre. I didn’t want to play in D’amour et d’eau fraîche because it was the first one I had directed – I was scared it would be too difficult for me.

-

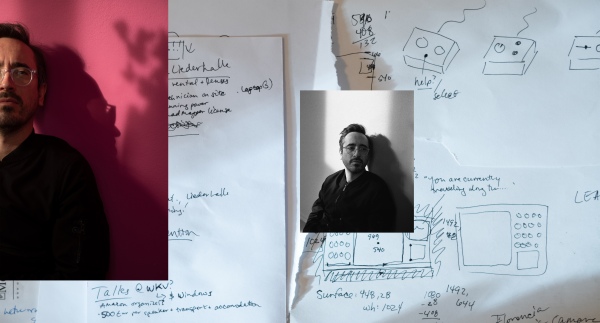

What are the things you are working on, while at the residency at the Ujazdowski Castle?

- I am continuing my research, working on the BIG biennale, and on a project in a theatre in Geneva, which we are launching in December. So I am working a lot; I write, make films and discuss, and try to get my head around the current situation.

-

What are your next steps?

- In December I am going back to Geneva, where we will present a theatre project called Nous sommes partout, making a very strong and useful bridge between institutional art and activism.

- Warsaw, 9 November 2020