talk

Music found in the city

Nick Yulman, artist and musician whose latest album Warsaw Machines & Songs features instruments found in Warsaw, talks to Anna Ptak

- The instruments you used while recording Warsaw Machines & Songs include, e.g.: a fibreglass helmet suspended on strings from the ceiling, books selected in view of the sound they produce when drummed, kalimba-like instrument built from scavenged wires. Could you tell me how some of these objects have found their way from the streets of Warsaw to your songs?

- The instrument that resembles the kalimba, an instrument of a family of African lamellophones, is made from fibres that fell out of the mechanical street sweeping brushes; they are tuned metal plates. Living in Brooklyn I once noticed that street sweepers not so much clean the streets as they scatter rusty metal pieces around the city. While looking around Warsaw for materials to build the instruments, I began to find these characteristic metal strips. It is such urban scrap that interests me, things that are strangely familiar: personal landmarks. Using seemingly useless or worn materials to build something that embraces beauty and complexity is a pleasure in itself. Putting these bits and pieces together and processing them into machines and robots goes beyond handicraft, random quality of the material; computer-programmable devices are precise and controllable, which is not suggested by their very design. You have also mentioned books – the very act of collecting them was very relevant, too. I quite frequently visited a second-hand bookshop in Warsaw. I looked through books with no price tags on them and eventually chose a few - just because of the sound they produced. I am positive that in terms of content it was a very strange mix. And when I was drumming them, the seller said that because they were antiquarian rarities they would cost me dearly. And he led me into the back room, where there was a box full of communist literature - all of these books were on sale for as little as one zloty.

- The picture of housing estate garages on the disc cover is very meaningful. Did you know that garages had used to be the venues of Polish men’s DIY and inventiveness based on resourcefulness?

- No, I didn’t!

- Building instruments from scratch is not a shortcut to playing music. You compose and sing songs playing your own handmade instruments. A one-man band is quite an archaic figure in today’s art. Do you intend your practice to legitimise the DIY attitude?

- The city as a resource or ecosystem from which to draw materials also appears in my social issue-oriented works. For example, No Bills is such a project, developed in collaboration with the North Brooklyn Public Art Coalition in my neighbourhood, i.e. in Greenpoint and Williamsburg, where I collected stories of the local residents, business owners, local activists and people representing the voice of the community. These recordings were presented to the public in the form of a sound installation placed on the fences of construction sites. One striking feature of this area is its large-scale development that had taken place following a complete makeover of the spatial development plans. The sites, historically associated with manufacturing, small businesses, had been turned into residential sites with high-rise apartment blocks towering over the district. So it goes - in every block of streets there had appeared fenced construction sites. And along with them the ubiquitous warning signs that you can always see on fences – “post no bills” - no posters or advertisements. We gave passersby a chance encounter opportunity, inviting them to listen to stories about the place that was currently under transition. In a fairly direct way we wanted to refer to the history of the area at the places most expressly manifesting its transformation. Hence the idea to make use of the fences, literally, as sound boards for public conversation. These constructions, rather than being completed within a year or two as planned, had had to be discontinued due to the said land-use plan modifications and the ensuing investment projects being badly hit by the effects of the economic crisis. Many sites remained at a standstill for years. Through this project we took over this area, the sites separated from their past – they are nothing but holes in the ground - to bring in some form of life and history.

- This kind of documentary approach was also part of your job in the The StoryCorps project. Could you tell us about this action and its objectives?

- The StoryCorps is an oral history project which consists in collecting interviews across the United States. I worked on it for a long time, travelling around the country, recording interviews with different people. In a nutshell it is about collecting and preserving life stories told one another by two persons who talk about what they have at heart. The project is based on the assumption, or ethos, that two people who know each other and share some knowledge of their lives, interests, expectations and dreams, will create a document that is different from that of a historian or journalist who would ask questions. Naturally, such a situation involves a mediator, a host who operates the recording equipment, controls the recording by asking further questions, makes sure that the conversation – say, between child and parent – is more comprehensible to people unaware of the context in which the interlocutors are immersed. The purpose of this project is formally defined: to build an archive. The recordings are collected and archived at the Library of Congress, they also provide material for shows broadcast on the National Public Radio. The project’s mission, as formulated by its originator, Dave Isay is to promote the culture of listening. The project was launched shortly after the start of Bush’s second term in office, at the time when the sense of the gap between Republican and Democrat supporters, conservatives and liberals, was exceptionally severe, when no dialogue seemed possible. It stemmed from this. Of course, such a problem cannot be solved unilaterally, but the project is a good reminder that sometimes you need to step back and try to get a grasp of our common experience, some elements around which we unite, rather than look, whatever the price, for what divides us.

- On Bone Conductors: Twitches, your first record, there is a piece that caught my attention: “I survived, because I used my ears”...

- And I stick to that. I think that at the time I wrote this song, I literally lived by listening - made a living recording, I was formally a sound worker. Though this phrase, of course, also affects the idea of active listening. It is not very often that we wonder how we could use our ears, although we do think what to make with our hands.

- How important is the relationship between the sound and place in your installations and recordings? Do you want to keep this relationship, extract the indigenous nature of the sound to tell your stories? For instance, what is your attitude to the traditions of recording musical manifestations of American culture, as exemplified by Alan Lomax?

- The tradition you are talking about is obviously a point of reference. And its exploration certainly induced my interest in recording. I would also mention a great oral histories collector and troublemaker, Studs Terkel. This method of documenting the “folk tradition” stems out of the curiosity of what it is like, but in effect produces it. After all, there are known stories about Lomax’s band looking in prisons for songs that would correspond to their idea of the rural South, while one should rather think of something that better suits the everyday life of these places and people. The working method is part of the recording, but I am not looking for neutrality. No matter how much I liked the StoryCorps approach, for me it is the experiment – for example, inclusion of oral histories into robotic music – that will be more interesting. For someone guided by the archival impulse this may seem reckless. Except that I am not guided by the purity of that impulse, the need to document history, rather by the need to create slightly confusing works that would reflect the isolation of the recording process. You get a grasp of the essence, but you also create using a medium that helps emerge other forms of life, movements and reconfigurations. Both these attitudes should illuminate each other. Especially when you’re dealing with such a dense matter as the city. Many sounds recorded in the city are woven into the music on Warsaw Machinery & Songs. One of the songs is based on larger fragments of the recordings, of course there is a lot of editing, looping of the voices, finding the melody in them. At a location, whose language you do not know, language and sound are more independent from each other. While in the Ujazdowski Castle, I started working on a project titled Panaudicon. In Warsaw there are so many places that are formally referred to as castles or palaces, I thought, it would be interesting to visit them all and overlie the recordings of these visits on each other, creating a simulation of ubiquity in these - at least nominally - seats of authority. I also reached the Presidential Palace, on April 10, the day of the presidential plane crash, on the day of mourning. Being in that place in the middle of someone else’s national tragedy, feeling it and yet not being fully aware of what I was witnessing, was a bizarre experience. And that place sounded in a very special way – this kind of observation seems to be completely superficial, yet I could not stop hearing such details as the sounds of metal caps falling off the candles and onto the ground everywhere. And that sound is on the record, in the song in which you can also clearly hear the instrument built of the metal plates.

- As I understand, you try to avoid categorising what you do into field recordings, performances involving machines, sound installations, etc.?

- For a long time it was like that - they were independent disciplines. But I think that creating links between the things within our area of interest is inevitable. The workshop I held in Warsaw was the first attempt at a literal combination of these disciplines. The participants brought various objects, talked about the relevance of those objects from which we later built the instruments. The result was the song installation which plays the background music in the song. And if I were to specify what sound space I am after, I would say it is one in which the human presence is blurred. A voice separated from its body through recording, a machine that represents a kind of life or personality - is in some way present for those who come to see the installation. Field recordings utilising the binaural recording technique is yet another manifestation of this interest expressed through operation of the machine, as well as my favourite way of seeing new places. When I put on the microphone – because, technically speaking, the microphones are in your ears – I remember to pay attention to details in the sound landscape. When the recording is controlled by interests, say research interests, but also by how you move your head, passive perception becomes the active function of the documentation.

- These hybrids, installations, robots and machines play catchy melodies. Finally, let’s go back to the song - why is the song your primary means of communication with the listener?

- I am now working on an installation titled New York City Immigration Song. It is a physical, tangible version of the data representation programme I have written, in which the history of immigration to New York, or rather the data representing this history, is assigned specific sound values. Imagine a world map with a network of strings stretched from nodes across it to a central anchor point located at New York. The distance is a musical note, the sound of the string, I have also set some rules relative to, for example, the number of immigrants living in the city in the given census year, I use the sequence of years like a metronome. The tune is quite abstract, but calling it a song I evoke certain mythology associated with immigrant cultures. For most people, the presence of immigrants is sensed on the level of cultural gifts: music, food. In this project, I would like to use the sound for data analysis - indeed quite a common sound design technique. The 150 years represented by the data will have a different sound profile if they are listened to for two minutes, and still different when listened to for 30 seconds. The inconsistency of this data set is quite frustrating. With the passage of time the criteria changed, different questions were asked about who lived in the city. There are periods of time when the whole of Africa is represented by just one point or no not at all. Working on these data, I have to refer to these deficiencies and find a way to make these omissions clear. Generally speaking, when I write songs I imagine them as data stores. However, in roundabout way I go back to pop and folk songs. Musical robotics is more associated with experimental forms or new music, but for me it is more interesting to use it in the available form. I love John Cage, but this tradition is a far cry from what I do. I do not pretend to say revealing things about songs. They are important and that is all. In contemporary art they are used as cultural markers exploiting the cultural connotations of popular music. Although it is also interesting, I am more into the form of songs. Their recognisable structure is a serious matter. A strong structure that can withstand a variety of treatments, tampering, while sound abstractions must be handled with more care. Taking a song as an input, you can convert it in many ways, leave your footprint, and still keep up its final entirety. The inalienability of melodic songs has caused them to be an important and effective medium of ideas, and for me - a great starting point for experiment.

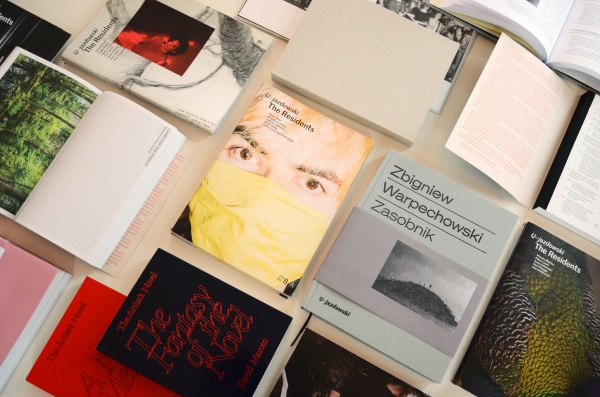

Recommended

Today at U–jazdowski