Co-ordinates from the middle of nowhere

Dani Ploeger in conversation with Phoebe Blatton

-

Can you tell me a bit about your background?

-

I have always been interested in new technologies. I was already a geek when I was little. I started programming on a computer when I was eight years old or so – just little programs in BASIC. At the same time, I played the trombone in the village wind band. I ended up studying classical music, but I was always headed towards contemporary and experimental forms. I became increasingly interested in electroacoustic music and experimental music theatre, the work of composers like Vinko Globokar, Mauricio Kagel and Alvin Lucier. When I eventually started making my own pieces, my work in sound and performance art came together with my early fascination with digital technology. Over time, this has developed into a more cultural critical project in which sound plays a less prominent role. In my current work, I try to dissect the ways in which ideologies of progress and innovation are inscribed in the technologies of the everyday.

-

-

Considering your background in performing arts, was your interest in coming to Poland in any way related to the country’s history of performance and theatre?

-

Not really. My interest in coming to Poland was mostly connected with one of the themes of my current work: How are the language and iconography of consumer technology used in relation to warfare, violence and control of borders? Over the past few years, I have been working on a project that looks at the fences that have recently been erected on the outer borders of the European Union. The idiom of high-technology is often used to make these fences seem something other than what they are. For instance, the Hungarian government has issued press releases in which they call the fence on the Hungarian-Serbian border a ‘smart fence. The use of the term ‘smart’ suggests that it fits into the same paradigm as the ‘smart home.’ In this way, the description of the fence connects it to the ideology of advanced technology as a sign of progress, rationality, and ultimately a sense of inherent justness. However, the reality of this fence is that 95% or more of it is actually very low-tech razor wire. In the end, the fence is not very different from the iron curtain that stretched across Central Europe a few decades earlier.

-

-

-

-

[Looking at a piece of the razor wire] This is really vicious, isn’t it?

-

It’s terrible. The Spanish company that produces it has made their fortune from the construction of the Spanish border fences in North-Africa. On their website, they present themselves as a stereotypical, late-capitalist business. They have generic-sounding corporate values that are just like those of any other company. The first one is, ‘We act with loyalty, professionalism, and respect for people.’ You can click on a button to buy their product ‘quickly and safely’ in their web shop. This is how I bought the piece you’re holding. In other words, there’s a cognitive dissonance between the world of slick entrepreneurship evoked by their website, and the violent technology they are actually making and selling.

-

-

Can you say a bit more about your interest in Poland in relation to your work on borders and technology?

-

I have been very interested in Poland because it seems to be the border country par excellence. It might be the European country with the most multi-faceted and turbulent border politics, both historically and in the present. There’s the border with Kaliningrad. Whenever the Russians build a new shed in an army base there, panic arises about supposed military threats. Then there’s the Ukrainian border, which is notorious for smuggling cigarettes and other products, including people. The Oder-Neisse border with Germany, drawn up after the Second World War, has recently been challenged again by some German right-wing politicians. But the border I’m most interested in for my current work is the border with Belarus. In recent years, there has been an issue about swine flu. Wild boars carrying the disease have been infecting pigs on Polish farms. In response, the Polish government has been toying with the idea – which has now been shelved for the time being I believe – to build a fence in the East of the country to prevent wild boars entering from Belarus. The theme of a ‘threat from the East,’ which seems to play a role in the way this issue is talked about, has really triggered my interest. It reminded me of campaigns against grey, ‘American’ squirrels in the UK, who are threatening the survival of the ‘native’ red squirrel. When you look closer at the backgrounds and motivations of the people who are active in this movement, it often becomes clear that it’s not just about ecological preservation. The concern with nature is often part of a broader and more complex set of sentiments about feelings of insecurity, patriotism and xenophobia in the context of a globalised world.

-

-

Has there been a particular area or place that you have been looking at in this context?

-

Following my interest in the planned boar fence, I started looking at Białowieża Forest, one of the last remaining primeval forests in Europe, situated on the border between Poland and Belarus. From there, the project has shifted into a slightly different direction. In tourism slogans, the Białowieża Forest is often described as one of the last examples of the ‘original Europe,’ a pristine place where you can supposedly travel back in time to the good old days before the hectic life of contemporary culture. I became fascinated in how the Forest is promoted as something at the very opposite end of the spectrum of urban life, almost like an idea of going back to a pre-cultural condition.

-

However, the paradox is that the itineraries of tourist trips that are promoted like this actually rather tend to follow the logic of spectacle, very much in the way Guy Debord describes in his book The Society of the Spectacle. You get up early in the morning to get to the best spots, where you will have a unique opportunity to spot bison and see some really special trees, etcetera. When I visited the Strict Reserve of the forest in December, I wanted to go on a hike that would follow the idea of the ‘dérive’, a walk led by a meandering approach, rather than a focus on highlights and curiosities. However, the guide seemed unable to go ‘off script’. At some point in the forest his phone rang. There’s actually reception in the forest. It was his wife calling, and he told her, ‘Yeah, we’re just at the second oak now.’

-

While you are promised a trip into the primeval wilderness, you are actually entering a tightly scripted performance. This is the crux of what I find interesting about Białowieża. In addition to the nation state border with Belarus, the forest also seems to harbour a kind of nature-culture border that is represented and performed in all sorts of ways.

-

-

-

-

Can you say more about the idea of ‘space’ in relation to the perceived or enacted border between nature and culture?

-

Apart from mobile phone reception, there are other high-tech things that influence the way you experience being in the forest. At the entrance of the Strict Reserve there are signs pointing out that there are CCTV cameras inside the forest to check whether people are obeying the rules. While I was walking around in the forest, I kept looking in the trees to try to spot these cameras. At the same time, I had a sensation of being constantly observed, very much in the sense of what Jeremy Bentham says about his panopticon prison design. In this, the guards can observe you from a point where you can’t see them. As a result you always feel observed, regardless of whether somebody is really looking at you or not. In addition, like almost everywhere in the world, there are GPS signals in the forest. You can always look on your phone and know exactly where you are.

-

I think that these things fundamentally change the way we experience space in the forest. In a way, the sensation of being ‘in the middle of nowhere’ no longer really exists. This is one of the things I am working on during my residency. I am experimenting with a device that can generate fake GPS signals to let your phone show that you are in a different place from where you actually are. Another thing I am looking at is whether it is possible to get hold of video footage from the cameras in the forest to use in my work.

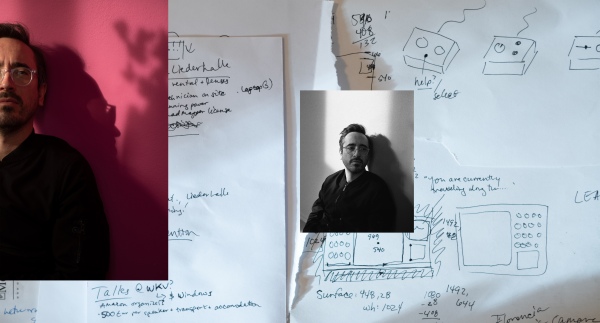

Dani Ploeger on a residency at U–jazdowski. Film: Marta Wódz