To travel down the river...

Pierre Coric in conversation with Phoebe Blatton

-

Can you tell me about your interest in the River Vistula?

-

I have been researching many aspects of this river, such as the sand, which has been used a lot in Warsaw for construction. The castle could essentially be made from blocks using this sand. But I think the energy involved in transforming the sand is far more important than the object itself. This sand is appealing for me because it is inert and has a mono-semic quality, but can become poly-semic things: glass, for instance, which can be fragile and beautiful. This type of glass – when you drip it in cold water, it becomes solid but in a very specific way. Under heat, it won’t break, but if you scratch it, it can vaporise and return to sand. I think that is really amazing, these different ways of structuring energy. Sand can become mud, or concrete, or bricks, or glass – such a range of functions. I’ve been researching glass making, and there are all these people with this crazy knowledge...

-

-

Are you interested in this idea of making, of the ‘artisan’?

-

Yes. I’ve been thinking about the artist and artisan, this separation... I wish it was less; that they could really collaborate closely. It’s almost a matter of point of view: one person does something on their own, for ‘no reason’, so this person is an artist, whereas another person does things that are ‘useful’, so they are an artisan. However, the artisan also has a practice, and reflection – they spend time, they work on their designs, perfecting specific tricks to make them better. So, it also has this quality, this progression, similar to an artist’s life.

-

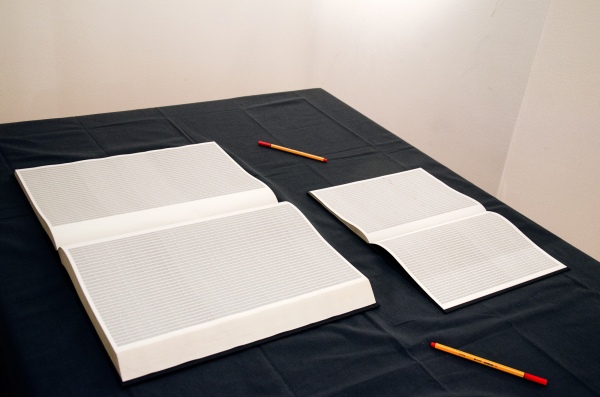

I’m trying to work with artisans in a more horizontal way. You arrive at a protocol when creating a piece – maybe you could make it yourself if you spent 10 years practising – but if you do it with an artisan, not as an assistant, but as a collaborator, it becomes a much better process. I made a huge wall painting, which of course I could have done on my own, using assistants. But I did it by making a machine that gives instructions on how to make it, and then, by using the instrument together, it becomes a collaboration. It is still my project, but we did it together and the process was really enjoyable. I was trying strategies to involve other people fairly.

-

-

-

-

Are you bringing these thoughts to the river project?

-

So far, I have just been gathering information, keeping everything super broad, meeting various people, including small communities that have special knowledge, like these people who build boats. What I find interesting about the Vistula is that it’s still pretty wild. It’s not used for traffic. When you see how wide it is, and how far from the sea, you’d imagine big boats bringing containers to Warsaw. I find it very precious. This emptiness, the possible freedom for people to enjoy the river in a natural way. They can go from Krakow to Gdansk downstream, without a motor sometimes, just a raft to travel down the river, just for pleasure.

-

-

It’s not often you can do that in a capital city.

-

That’s why I think Warsaw is special. Because of all this contrast between city and nature, between city and city centre – you have these tall buildings next to communist blocks, this really high changing frequency.

-

-

-

That makes me think about usurping previous histories. Take the church at Plac Grzybowski, for instance. When the communist blocks in that area were built in the 1960s, the planning was designed to hide the church – because it was communist times and a church could not be strictly approved – but they had still allowed the church to be rebuilt in the 1950s. There was a scandal involving the priest who was responsible for rebuilding it, and who was eventually killed in prison. But thinking about the ‘changing frequency’ of buildings and landscape, the city planning was designed to hide the church, and then there are new buildings which are also hiding the communist buildings. These vertical layers are happening. How far can you go?

-

I’ve been thinking about this. As a side thing, I would like to make an atlas of high points that you can reach for free. Because it’s a privilege to be up high. At the same time, building something higher and crushing something smaller... people living in these blocks have the privilege of being high, while others are in the shadows of the higher buildings. I thought it would be cool to have a kind of secret map, an open collaborative map where you could say oh, I found this nice building you can enter for free through this door and find this view.

-

But to go back to the river, I was researching many different elements, water, wildlife – I saw a lot of evidence of beavers on the river bank. Beavers are the second most influential species on the earth. There used to be way more, but they have been killed for their fur. A lot of people have been critical of beavers, because they create dumps in swampy areas, but the areas become fertile and filter the water. Bacteria develop and feed the flora. They’re one of the key species of the ecosystem. When you remove them, the bacteria and the plants die, and so some people are trying to reintroduce them as a fixing species. Like re-planting trees to suck up the carbon. I like this idea of collaboration with different species. Being inspired by and learning from the beaver! The way they cut down trees, for example, waiting for it to fall with the wind, it’s good for the way forests regenerate.

-

I have a meeting with a biologist here, to learn how to use a microscope and spot all the little algae and bacteria. So far it’s been fun to have an overview of the river’s ‘actors’, living and non-living. The beavers, the sand... I don’t know where I’m headed, but I have an idea of holding an intervention involving beavers. I actually have a toy beaver in my pocket. I was in Liverpool and I found it in the street, and now I have started to carry it around everywhere. I had never thought about beavers before, but now that I’m here and have started researching, I think about the coincidence that I’ve been carrying a beaver in my pocket all this time!

-

-

-

-

Like a mascot?

-

Yeah! My partner and I always take him with us on travels, but it took coming here to finally read about what beavers do! They are doing great work. Considering all the ideas and stories around the river, I also heard a story about farmers storing cows on the islands in the middle of the river, so that they wouldn't be stolen! I have a funny picture in my mind of the innocent cows stuck on the island, just looking at the river passing by. That’s what I’m interested in, the river has all this physical resistance, but every element has a crazy amount of symbolism. The stream, the river, it is sometimes a road, or a border between two sides of the river. It has numerous intricate elements.

-

-

I think there are various legends as to how the mermaid became the symbol of Warsaw. One tells of her living in the river and helping the fishermen against an evil baron who was trying to control everything.

-

I read another, something about the statue of the Syrenka, that it’s made from the face of a Warsaw poet who was also a nurse during the uprising. That brings me back to the language element running through my work. I was thinking of writing something in the landscape, using sticks that have been cut by beavers, making flags, using the international maritime signal flags to create a sentence going along the river, or through the river. Preferably it would be a line of flags going across the river, saying something about the beavers and the cows, the people and bacteria. A statement that can be seen only if you pay attention to it. It would be an appealing, colourful object, and would hopefully play with and stand against this nationalist thing happening here, where there are so many Polish flags! You cannot write a sentence using only one letter! Telling a story requires more than one dimension.

Pierre Coric on a residency at U–jazdowski. Film: Karolina Sobel, Marta Bogdańska