The separation between virtual and real is an outdated concept

Ivan Svitlychnyi in conversation with Phoebe Blatton

-

What you are interested in doing at the Ujazdowski Castle?

-

For me, residencies are all about thinking, because when I’m in Kyiv I work a lot, and I don’t have time to do much thinking. I don’t like residencies where there’s pressure on you to come and do something, then leave. Where you leave your normal environment; you do your work, arrive in another city, in another situation, in another context, and then have a month to do something. That’s super stressful.

-

I really want to look at the archive while I’m here, because the U–jazdowski’s archive is huge, and I love reflecting on the system of archives. Not what’s necessarily in the archive, but the system of how it has been created. When I visit an institution, I always ask about their archive. It’s the mind of the institution, and when you see how projects are stored with others and consider the relationships, it reveals just how the institution thinks.

-

-

The two exhibitions currently on display at the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art deal with archives. Bik Van der Pol have worked directly with the U–jazdowski collection, using a spoken word script and performative tours to ‘activate’ the works and their connections to each other and the present. It’s interesting to compare with Karol Radziszewski’s exhibition, where he displays an archive that many conservatives in Poland would rather ignore, or even destroy! Here the display is almost more traditional, but the very fact it is exposed is incredibly significant. I think about the degree of trust that’s required when considering the return of these exhibitions into storage. The archive has always suggested to me a kind of dusty safety, but of course it’s not so simple. Can you tell me about the last physical gallery space that you were involved in running in Kharkiv?

-

Kharkiv is a huge city. It was the capital of Ukraine from 1919 to 1934. We have a lot of constructivism, factories, research institutes and students. It’s a cool city, but quite difficult for artists, because there’s just one gallery and exhibition space. That’s why I, together with artists from the art group SVITER (Lera Polianskova and Max Robotov), tried to set up something there, in a beautiful old factory (our curatorial project TEC), где мы проработали два года. Here we organised free of charge studios for artists, a recording studio, and a series of exhibitions and festivals. However, it all ended after an illegal takeover, when we had to leave the space just in one day.

-

After that, we thought about how could we create a space without a threat of closure. While we were pondering, we realised that our main problem is searching for space, and that a physical space limits us a lot, through needs such as rent, utility bills, exposure lighting, equipment – it’s a never-ending list. On top of that, a specific exhibition space is not accessible to everyone. But there is an alternative, and maybe even, I would say, the best option – the internet.

-

-

-

-

Is that how you founded the project Shukhliada?

-

Yes. Shukhliada means ‘drawer’. Sometimes you have a project in mind, but you have to wait for better times before you can create this project, you have to ‘put it in a drawer.’ We started thinking about the physical boundaries of a small drawer, how it is small and cheap and you can risk it in the mind of the viewer. But the internet is flexible, it allows you to use any tools, create virtual objects, create a performance or story. We can create a physical site, but artists working with augmented reality can leave the physical space behind. The drawer is really about creating some kind of prism or view.

-

-

It seems like a way of finding concentration, of slowing down, in an (art) world where big budgets, international affiliation etc., are still seen as a marker of success.

-

Yes. You can stop really thinking when you have a huge budget and production team. The relation between the concept and the final result can get lost. You need to stop and change your view, think differently. This applies to the way in which we think about Shukhliada too. We’ve had our own plans, but after some years, other curators have suggested proposals, thinking about Shukhliada in their own way, and we’re very open to this expansion.

-

-

-

-

A lot of artists are thinking about what it means to be making objects, and how to deal with their physicality, in terms of exhibition, the art market, the archive.

-

Classic sculpture is not so interesting for me. I had an education in classical sculpture, and the whole time I wanted to make physical objects, but I was always concerned with the medium. Physical objects are super informative objects. In text, you build some story or you need time to read it, but sculpture creates an immediate image in your mind.

-

-

I have been wondering why governments might be interested in the visual arts, imposing their own agendas etc. Even those within the art world tend to be deprecating about our potential in this field to ‘influence’ anything. But when you put it that way, it seems obvious. When I visited Kyiv in 2018, there was a big discussion about the ‘de-communisation’ project, which involved destroying communist era monuments. One of the projects I looked at was an initiative to restore the Kyiv Crematorium ‘Wall of Remembrance’, completed in the 1960s, which had been covered in concrete in the 1980s. So, it was built and destroyed under the same political system, but of course within this system there had been a change of attitudes towards the monument.

-

Yes, it’s interesting. In Ukraine, we have stupid de-communisation. They destroy monuments, without considering whether the merits of each monument are interesting from an artistic point of view, or whether we need to change the conception of this monument. Things are destroyed and nothing happens. Nobody thinks that maybe we need to open some monuments that were actually censored by the Soviet Union.

-

-

-

-

Yes, it’s crazy to think that the soviet era provided such a vast range of aesthetic and artistic output, and that you can have this blanket response. But I suppose it is a cycle of smashing what came before.

-

Yeah, a classic story; I think that some people like to smash things.

-

-

In this sense, it’s interesting to think about how the ‘virtual’ can respond to the fate of art in the ‘real world’. Can you tell me about the latest project you’re working on through Shukhliada?

-

We are currently working with the artist Oleksiy Sai. For us, this exhibition is a sequential step in demonstrating and articulating the capabilities of a virtual institution (at the same time, we must bear in mind that, for us, the separation between virtual and real is an outdated concept). This exhibition also reactivates certain interesting questions for us concerning virtual original work, the ratio of the virtual original with the original of the "real" world, the archive, the inconvenient angles of institutions...

-

As for Oleksey, it is important for him to emphasise the precariousness / relativity of control. And how control can easily go from the visitor to the institution, and vice versa. This topic is also very important for us.

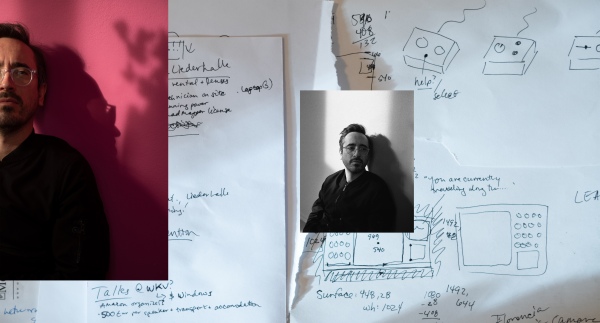

Ivan Svitlichnyi on a residency at U–jazdowski. Film: Karolina Sobel, Marta Bogdańska