Anna Orłowska

Sunday Night Drama

In a permanent refuge, the most important thing is the conviction of its impermeability. If only for looks, whenever one wants the eyesight – and the fantasy of a passive bystander appearing along – to rest and turn off from the rushing reality.

The past, especially of one’s dreams, borrowed – and unlived – seems to be one of these refuges. Pushing towards it is the Benjamin sentiment, which can be treated as a sort of escape from a complicated reality.

One example of such an escape is the fascination with the pre-war lifestyle of the privileged classes. It has been growing since the mid-twentieth century, along with a fashion for trips to British country residences and the popular literature of the era, British period dramas and films like Gosford Park, and finally the restaurants of Polish castles such as Pszczyna, Łańcut or Moszna. In all those places a need arises to look into the past, whose very depiction is the fulfillment of the promises of the "good old days,” in which the rules were simple and followed, the hierarchy of power unchanging, and the environment beautiful and sublime. Anna Orłowska, through the exhibition Sunday Night Drama, herself admits to cultivating such escapes and also to attempts of delicately deconstructing them.

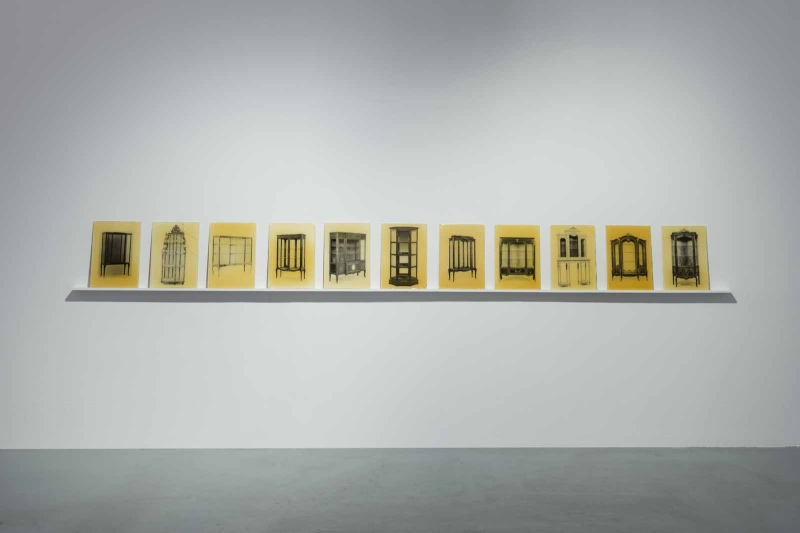

What is most significant in this trend, which speaks to the masses’ imagination, seems to be the palace with its complicated, box-shaped structure. Therefore, Orłowska takes a perfect image of a building together with its interior architecture as the starting point and frame for the visual deconstruction. It is her giving it the specific characteristics of a complex organism with two blood vessels; they are separated by rigid rules and doors hidden behind ornamented wooden panelling.

The first, belonging to the aristocracy, flowed through all the main rooms that today's tourists admire. The stylish interiors, ornate furniture, stucco – all bathed in light, to better show the wealth and status of the owners. In their surroundings, the piercing pace of contemporary life, counted with every second, is becoming almost perceptible. The palaces’ spaces were designed in opposition to this feeling. They acted as arenas wherein those in power manifested a discord over the effective, pragmatic approach to time itself. Hence the concept of the Leisure Class, proposed by Thorstein Veblen. Leisureness is a form that is realized through the acquirement and practice of useless knowledge – the complex etiquettes of rituals and gestures. An example may be the refusal to install a fixed bathroom in the palace, because the bathtub should be brought to its master. So your time and those of others was wasted – for show and in front of those who could never reach such a state.

The second blood vessel belonged to those who carried that bath; usually remaining invisible to tourists, and sometimes marginalized by researchers. It ran through narrow corridors, often hidden in walls surrounding the grand rooms, through the tunnels, into the windowless kitchens. There, time was counted directly by the masters of the household in proportion to the possibility of it being wasted. The servants were, therefore, along with the double architecture of the castle, part of the mechanism that allowed the leisure form to function. This all had to be carried out invisibly, so that leisureness itself remained light, with no apparent signs of effort.

Anna Orłowska discovers the complexity of this system, drawing attention to the omitted part of the ideal image of the palace lifestyle. In the course of ensuing visits to palaces and the exploration of attractions based on costume games, she discerns the often unconscious cultivation of this invisibility of the former servants in the activities of contemporary hosts. Many of the premises, even before the arrival of the restaurateurs, were walled or converted into offices, amputating half of the palace body. The artist understands the fate embedded in the very architecture of the objects, which in the moment of them being designed as well as now are trying to stop the visibility of the traces of the servants’ activities, sealing the permanence of this perfect image.

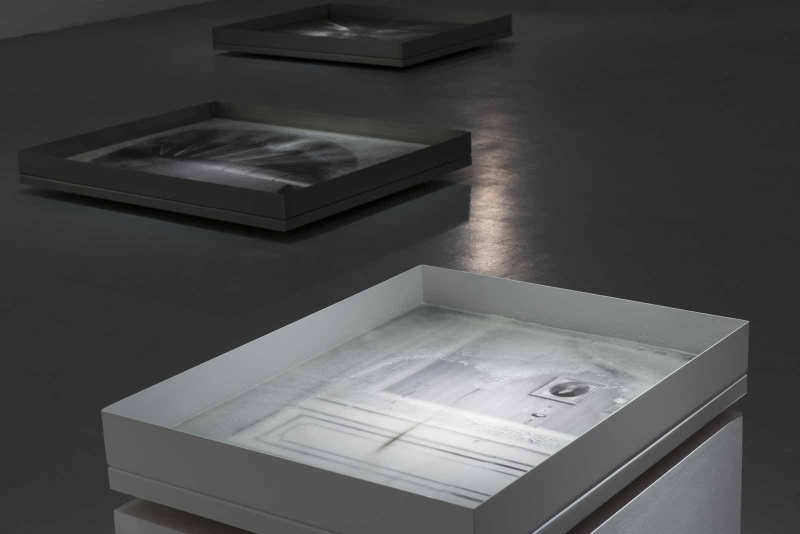

What is fascinating about escaping into the past of the palatial lifestyle, is a certain viscosity and sweetness accompanying the ideal image; the same escape, which we know from numerous guilty pleasures. In subsequent works of the exhibition Sunday Night Drama, Orłowska gives the viewer a variety of visual flavors, which may be unbeknownst to a tourist. Fragile, sugarcoated structures and moving images in paraffin baths make up the unknown face of a sweet refuge.

- Special thanks to the Castle Museum in Pszczyna, the Łańcut Castle Museum, the Museum in Nieborów and in Arkadia and the Castle in Moszna.

- Text

- Jakub Śwircz